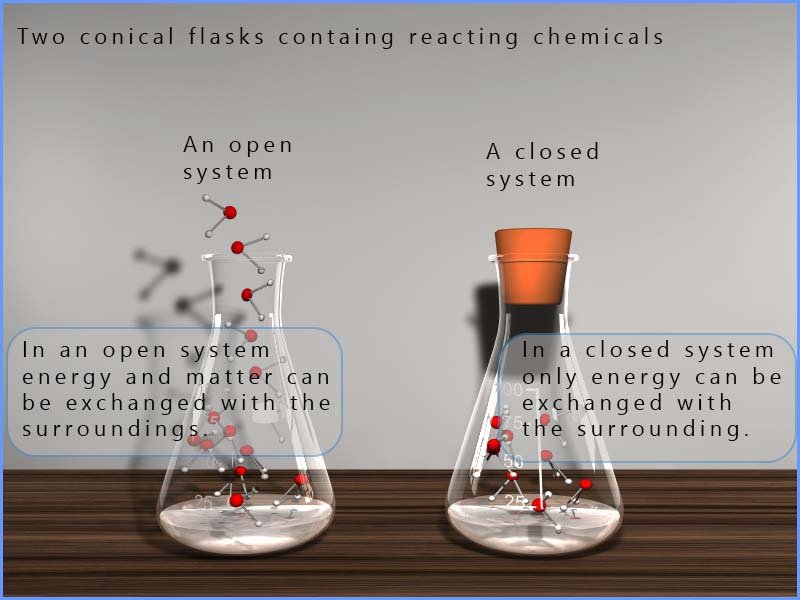

When dealing with chemical reactions we often talk about the system and the surroundings. The system is the reacting chemicals; that is the reactants and the products, while the surroundings are everything else; the beaker the reaction takes place in, the room, the building, the universe!

The system can be open or closed. An open system is one where both matter (the reacting chemicals) and energy can be exchanged freely with the surroundings. Carrying out a reaction in an open beaker or conical flask where, for example heat and gases can escape into the atmosphere is an example of a reaction taking place in an open system. A closed system on the other hand is one which can exchange energy (usually heat energy) with the surroundings but no matter is exchanged. The image below shows both open and closed systems. In the closed system below the rubber stopper will stop any matter entering or leaving while in the conical flask with no stopper both energy and matter can freely enter and leave the flask.

Click to open the button below if you would like a deeper dive into internal energy, enthalpy, heat and work. This is not needed for A-level it is just some background information and theory you may find helpful and useful.

Energy is a word which has probably been used many times in your science lessons, but what exactly is energy? The word energy is derived from the Greek word ergon, meaning work. A simple working picture of energy is the capacity to do work or supply heat.

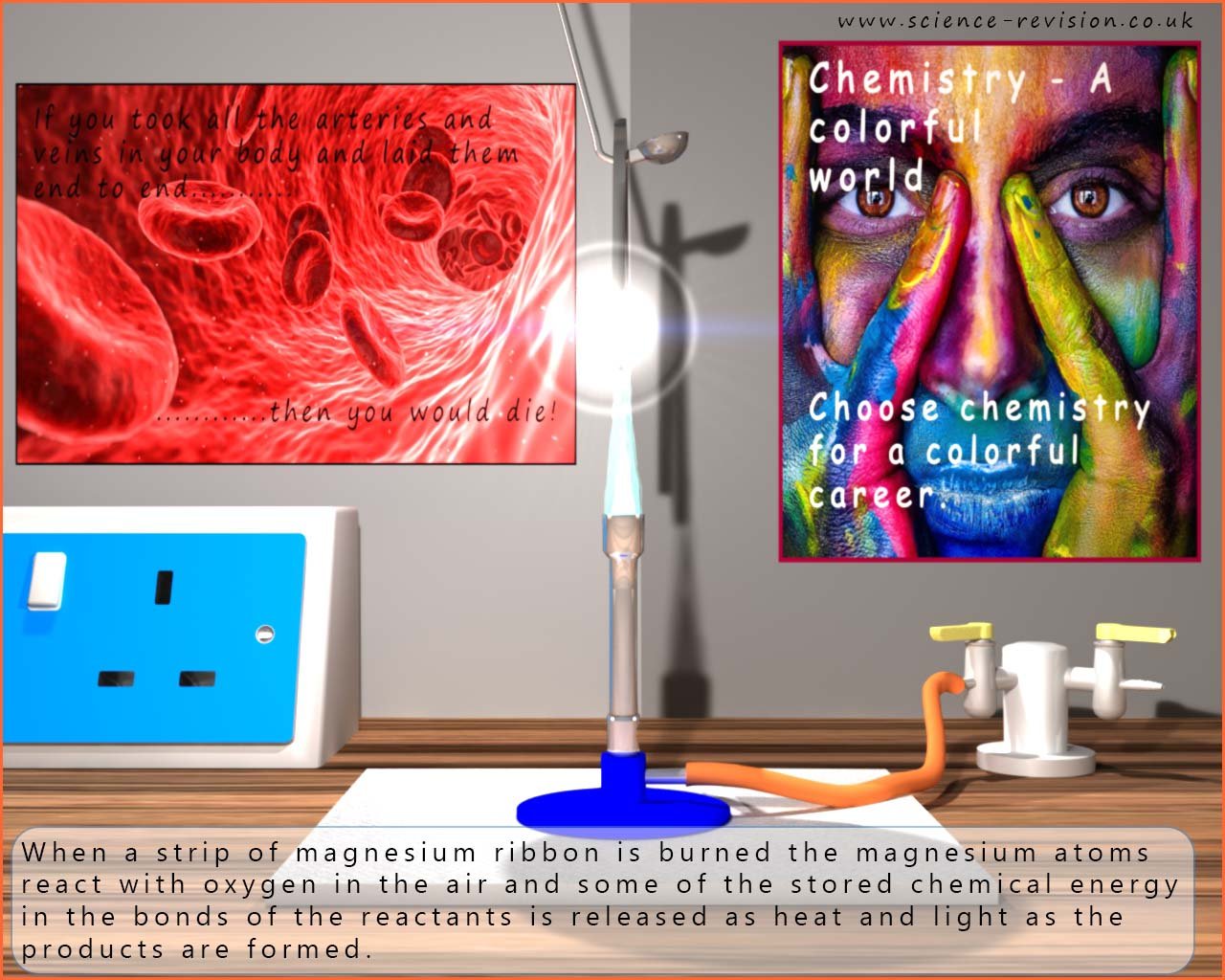

One of the main forms of energy we are concerned with in chemistry is potential energy. There is stored potential energy (chemical energy) within the bonds of molecules. When a substance undergoes a chemical reaction, some of this stored chemical energy may be released as heat and light. For example, when magnesium burns in oxygen, the reacting chemicals lose some of their stored potential (chemical) energy and transfer it to the surroundings mainly as heat (and also light) as products form.

Consider a chemical system (reactants and products). It could be a flask containing hydrogen and oxygen, or a beaker of acid reacting with magnesium ribbon. The particles in the system are moving, so they have kinetic energy. There is also potential energy associated with interactions and attractions between particles. The internal energy of a system (symbol E) is the sum of all the kinetic and potential energy of the particles that make up the system. It is not possible to calculate the absolute value of the internal energy of a real system.

From your GCSE science course you may remember that in physics we used a definition of work: work is done when a force moves an object a distance.

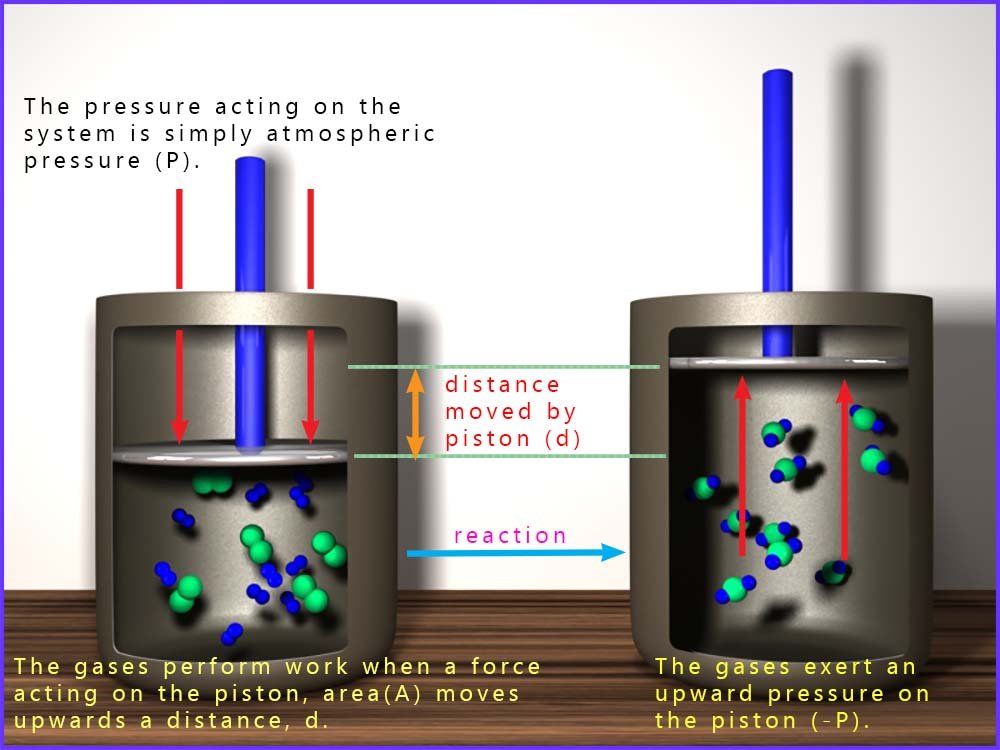

If a chemical reaction produces a gas, the gas can expand and push against the pressure of the atmosphere. This is called pressure-volume (PV) work. A common model is a gas reaction in a cylinder fitted with a movable piston. As the reaction occurs, heat energy may be released and the piston can be forced upwards by the gas produced. The gas applies a force to the piston, so the gas does work. This is outlined in the image below:

The force on the piston is:

Here A is the area of the piston and P is the external pressure (usually atmospheric pressure).

For PV work at constant external pressure, the work done by the system is given by the formula:

Here ΔV = (area of piston) × (distance moved) and the negative sign indicates that the system is transferring energy to the surroundings.

If the gas expands then ΔV is positive, so w is negative. This means the system has transferred energy to the surroundings.

So far we have seen that a system can exchange energy with its surroundings as heat and work:

Many chemical reactions are carried out in open containers at approximately constant atmospheric pressure, and energy can be transferred as both heat and PV work. For an internal energy change:

At constant pressure, the heat transferred from the system to the surroundings is written as qp, and since w = -PΔV, we get:

This formula can be rearranged to give:

In this expression E is the internal energy of the system. The PV term accounts for the energy associated with pressure–volume changes, such as expansion when a gas is formed, so that the enthalpy change corresponds to the heat transferred at constant pressure.

The heat transferred at constant pressure (qp) is the enthalpy change, given the symbol ΔH. Enthalpy is defined as:

Like internal energy, it is not possible to calculate the absolute value of the enthalpy of a real system. In chemistry, what is most useful is the change in enthalpy that occurs during a chemical reaction.

The enthalpy change (ΔH) for a reaction is the heat energy transferred at constant pressure. For many reactions, ΔH and ΔE have similar values because the PV work term is small.

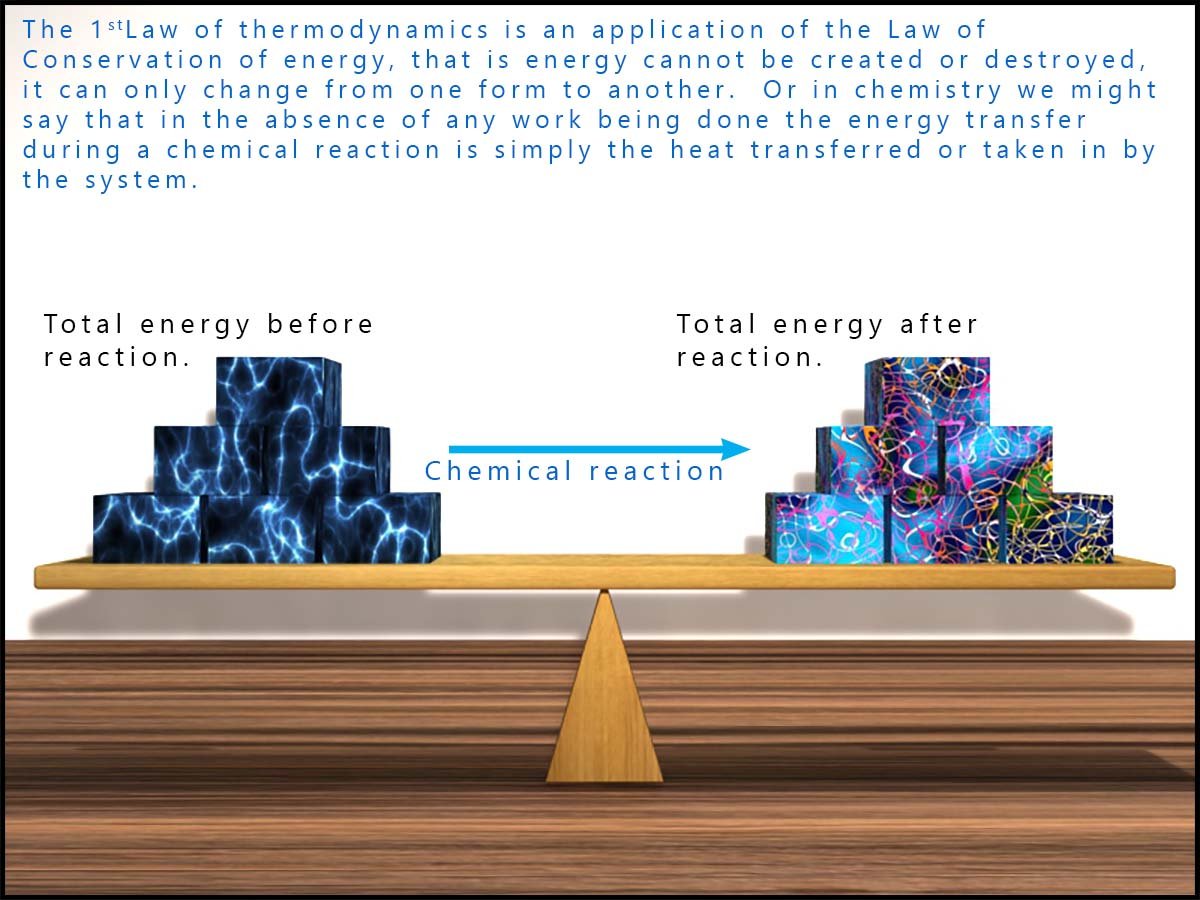

You should also consider the first law of thermodynamics when considering energy changes between the system and its surroundings. This law is based on the law of conservation of energy, which you probably first met in Year 7. The law of conservation of energy simply states that energy cannot be created or destroyed, only transferred between the system and its surroundings or changed from one form of energy to another.

For us chemists, this means that any energy lost by a reacting system is gained by the surroundings, and in an endothermic reaction any heat energy lost by the surroundings is gained by the system.

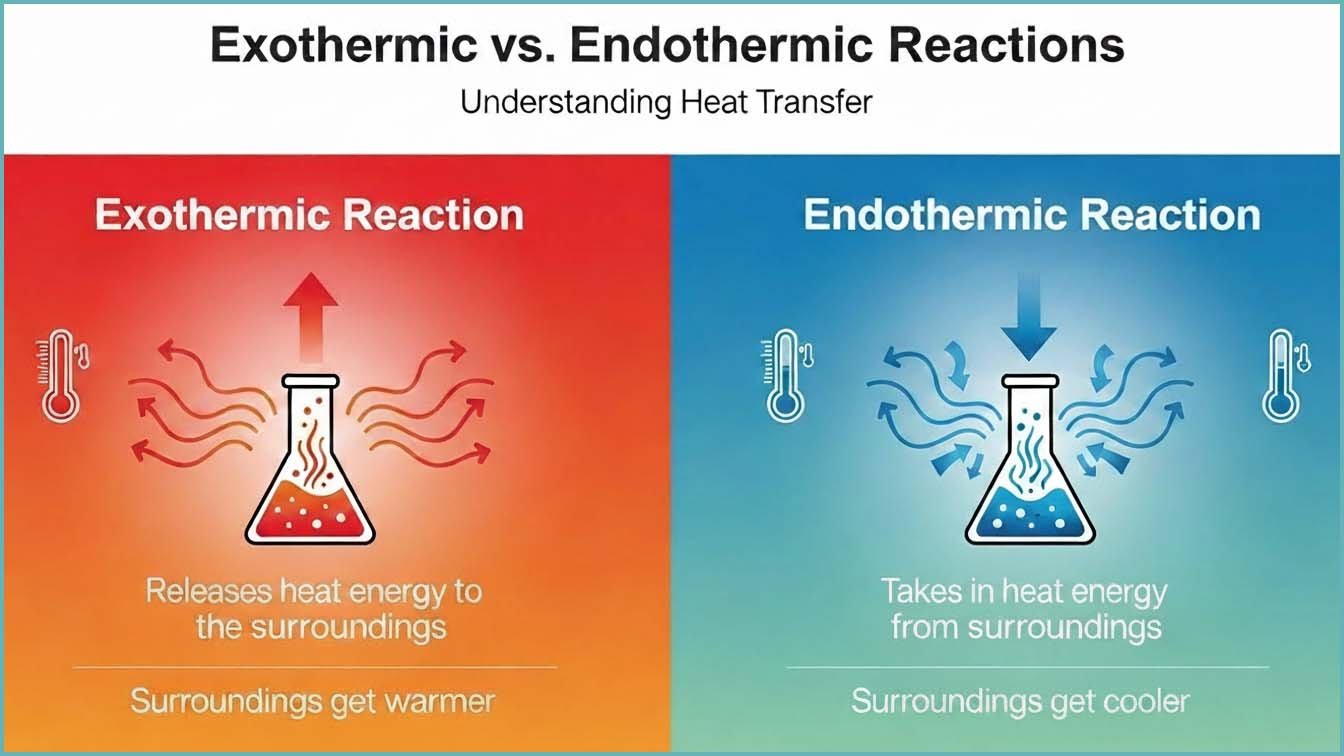

In your GCSE science course you will have met endothermic and exothermic reactions. In an exothermic reaction the system releases energy usually as heat to the surroundings and as a result the temperature of the surroundings increases. In contrast an endothermic reaction is one in which the system absorbs energy from the surroundings. This causes the surroundings to cool down. In both cases energy is conserved and is simply transferred between the system and its surroundings.

The table below contains a list of common exothermic and endothermic reactions you probably met in GCSE chemistry.

| Common exothermic reactions | Common endothermic reactions |

|---|---|

| Combustion reactions (e.g. burning fuels such as methane) | Thermal decomposition reactions |

| Neutralisation reactions (acid + alkali) | Dissolving ammonium salts in water (e.g. ammonium nitrate) |

| Metal reacting with oxygen (e.g. magnesium burning in air) | Photosynthesis |

| Metal reacting with acid (e.g. magnesium + hydrochloric acid) | Reaction of ammonium chloride with barium hydroxide |

| Respiration | Electrolysis reactions |

What you should know:

🔥An exothermic reaction releases energy to the surroundings.

A thermometer (part of the surroundings) would measure an increase in temperature.

🧊An endothermic reaction absorbs energy from the surroundings.

A thermometer (part of the surroundings) would measure a decrease in temperature.

Quick check: Would you expect the following reactions to be exothermic or endothermic?

Have you ever sucked on a sherbet sweet and felt your mouth getting slightly cooler? This is because there is an endothermic reaction taking place in your mouth. Sour sherbet sweets contain the weak acid citric acid and a base called sodium bicarbonate. In your mouth these chemicals react to release carbon dioxide gas; which gives the fizzing sensation when you eat sherbet but the reaction between the citric acid and basic sodium bicarbonate is endothermic. It removes heat energy from the surroundings (your mouth); so you feel a cooling sensation.

Endothermic reactions are much less common than exothermic reactions.

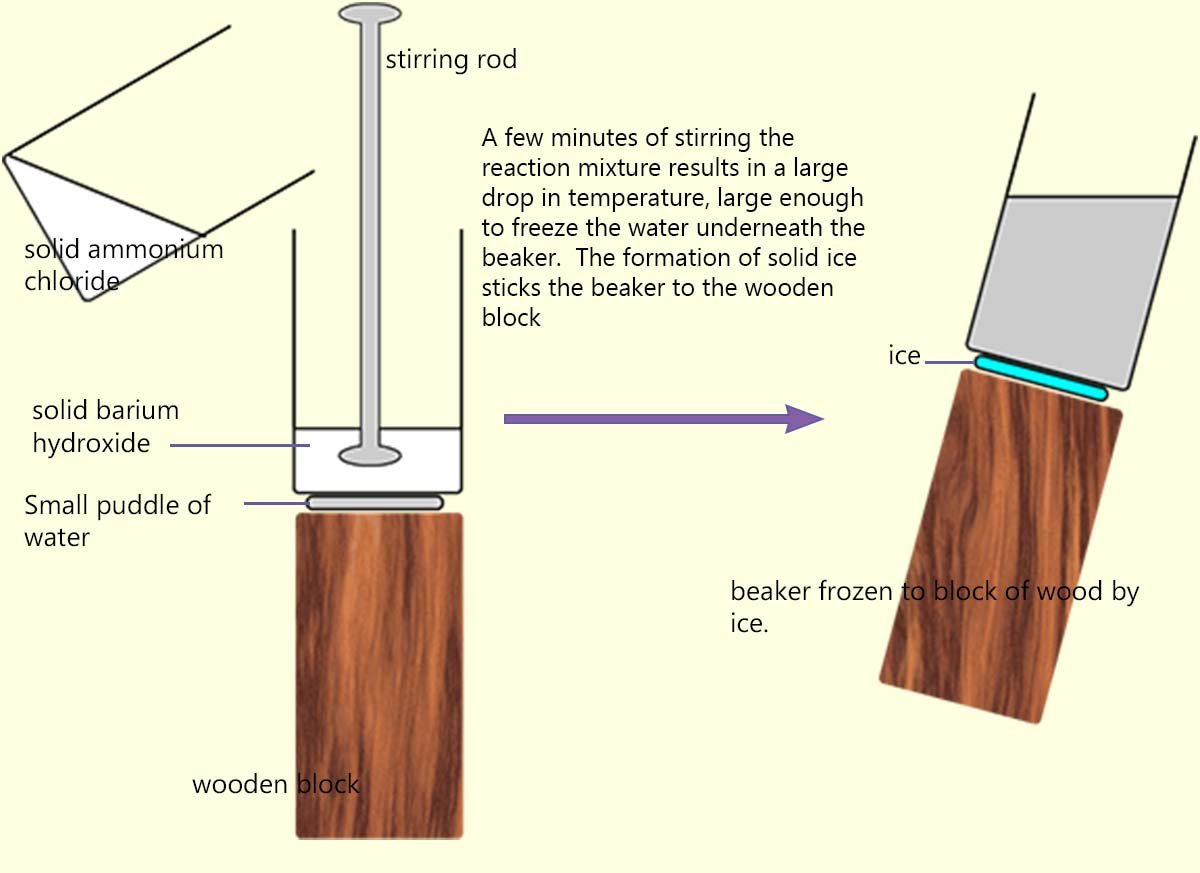

One of the most spectacular endothermic reactions is when solid ammonium chloride is mixed with solid barium hydroxide.

Here a beaker is often placed on a block of wood with a small pool of water is placed underneath it, as shown in the image opposite.

When the solids are mixed and stirred vigorously so much heat energy is removed

from the surroundings that the pool of water freezes and sticks the beaker to the wooden block.

One of the most spectacular endothermic reactions is when solid ammonium chloride is mixed with solid barium hydroxide.

Here a beaker is often placed on a block of wood with a small pool of water is placed underneath it, as shown in the image opposite.

When the solids are mixed and stirred vigorously so much heat energy is removed

from the surroundings that the pool of water freezes and sticks the beaker to the wooden block.

The temperature changes in this experiment are very large.

If the experiment is done at room temperature (about 25oC), the temperature of the reacting mixture can fall to around -10oC.

In this experiment the chemicals (the system) gain energy from the

surroundings, so the temperature of the surroundings falls.

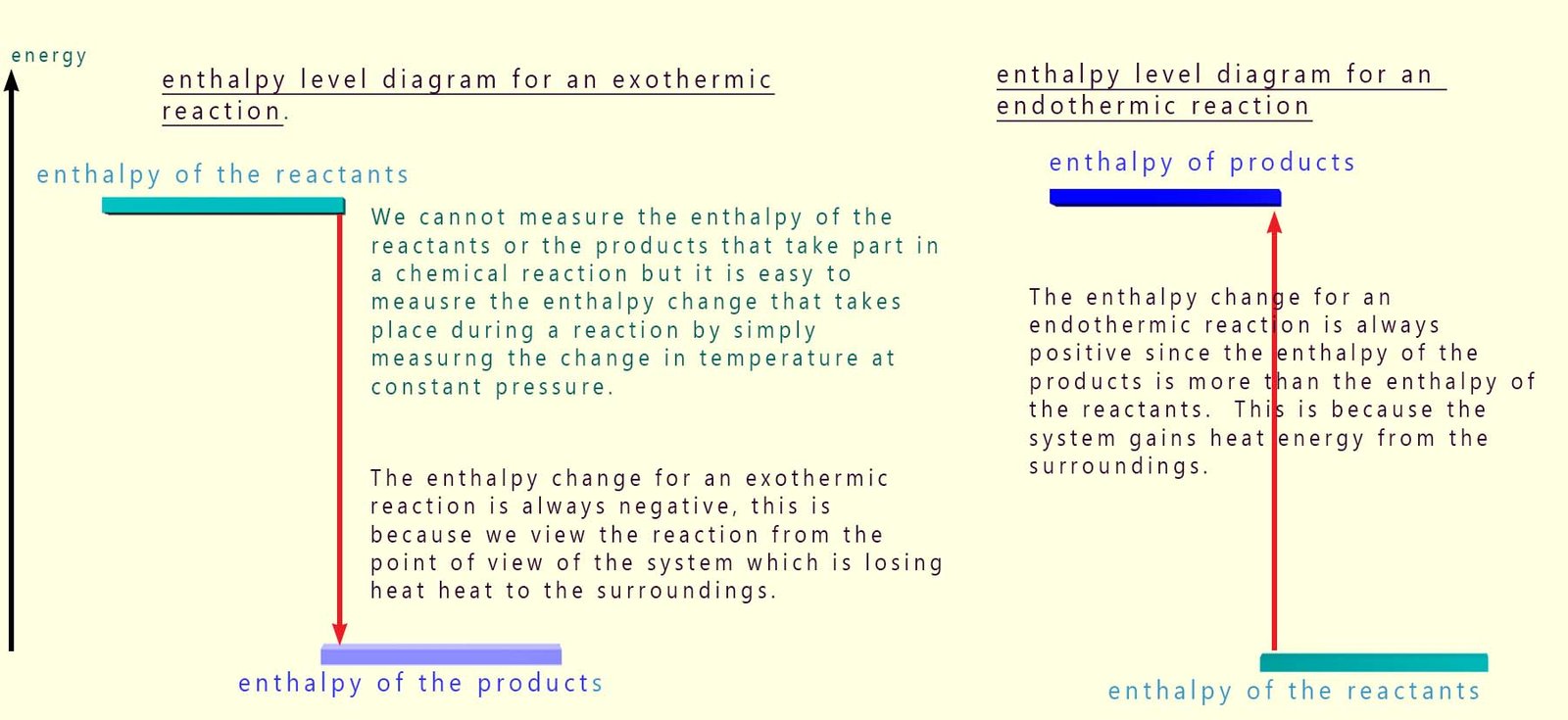

The image below shows an enthalpy profile diagram for

exothermic and endothermic reactions.

For an exothermic reaction, the enthalpy change (ΔH) is negative.

This is because the system releases energy to the

surroundings, usually as heat.

As a result, the enthalpy of the products is lower than the enthalpy of the reactants.

Since ΔH is defined as

Hproducts − Hreactants,

this gives a negative value.

For an endothermic reaction the

enthalpy change (ΔH) is positive.

In this case the system absorbs

energy from the surroundings.

This means the products have a higher enthalpy than the reactants so the value of

ΔH is positive.

Each statement below contains a common error. Identify the errors then press the button to check your answers.

Spot the mistake:

Each statement below contains a common error. Can you identify what is wrong?