Chemistry only

Corrosion is what happens when metals slowly wear away as they react with their surroundings. 🌧️ It’s a natural but destructive process; a battle between shiny, useful metals and the oxygen and water around them. The most familiar example is the corrosion of iron, known as rusting. When this happens, the iron atoms are oxidised — they lose electrons and form iron ions. This weakens the metal structure, causing bridges, cars, and ships to gradually crumble or fail if left unprotected. ⚙️⛵🚗

Rust itself is hydrated iron(III) oxide (Fe2O3·nH2O); a soft, brown coloured flaky compound that falls from the surface of theiron as it rusts. As it flakes away, it exposes new layers of fresh iron beneath, which then react again with water and oxygen. The process keeps repeating until the metal is completely eaten away. That’s why the corrosion of metals is more than just an inconvenience; it’s costly, dangerous, and one of chemistry’s most persistent real-world problems. ⚠️

The images below highlight some of the dangers and costs associated with the corrosion of metals.

Corrosion is the attack of oxygen and water on a metal. An equation to show the corrosion or rusting of the metal iron is shown below:

Iron(s) + oxygen(g) + water(l) → hydrated iron(III) oxide(s)

4Fe(s) + 3O2(g) + nH2O(l) → 2Fe2O3·nH2O(s)

Hydrated iron(III) oxide or rust has the chemical formula Fe2O3·nH2O. It contains Fe3+ ions; that is iron atoms that have been oxidised and lost 3 electrons, as well as oxide ions (O2-); that is oxygen atoms that have gained 2 electrons and have been reduced.

Hydrated means that the iron oxide also contains some water molecules which are associated within the giant ionic lattice structure of the iron oxide. The amount of water present is shown by the value of n in the chemical formula for rust; n is a small number usually between 2 and 3. The two half-equations below show the oxidation of the iron atoms to form iron(III) ions and the reduction of oxygen in water to form hydroxide ions. Overall we can say that the corrosion of a metal is a redox reaction where the metal is oxidised and the oxygen is reduced.

Fe → Fe3+ + 3e- – oxidation half-equation

O2 + 2H2O + 4e- → 4OH- – reduction half-equation

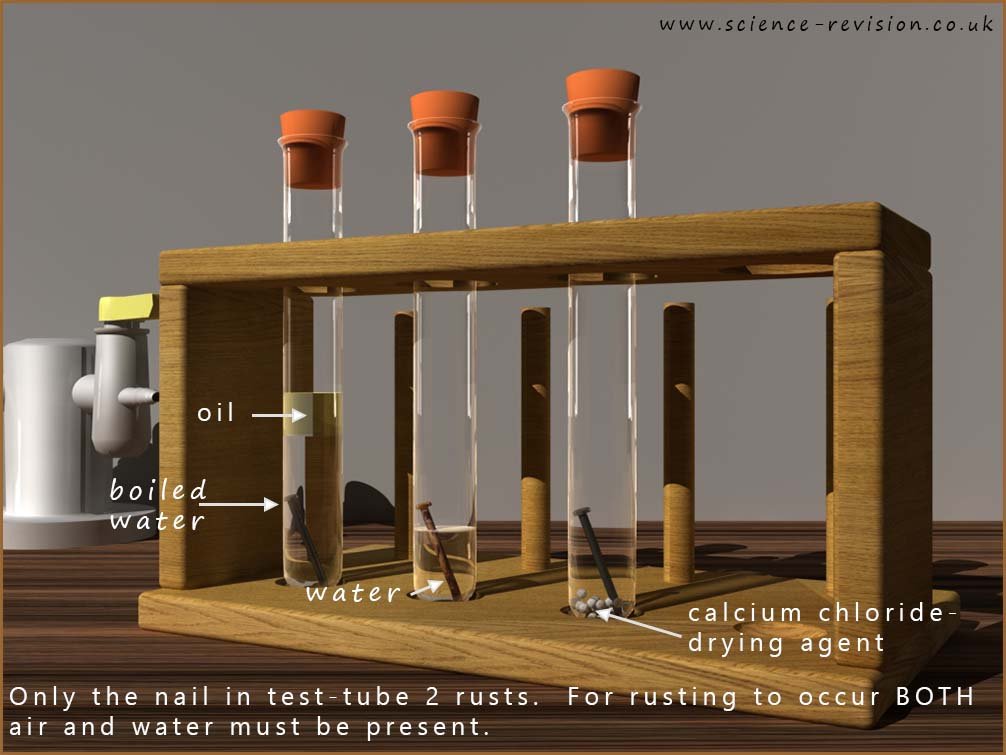

For corrosion to occur, certain conditions must be met. In most cases, both water 💧 and oxygen 🌬️ must be present for the metal to start reacting. Without one of these, rusting simply doesn’t happen. This can be shown clearly in the experiment set up in the image below; here three iron nails have been placed in three separate test tubes with slightly different conditions in each test tube:

This is a quick and easy experiment to set up and proves that BOTH water and oxygen are needed for corrosion to occur:

Complete the activity below by deciding where the item/object will corrode or not.

Click one of the situations below to select it, then click on a box: “Will rust” or “Will not rust (or only a little)”. When you’re done, press “Check answers”.

Click to select, then click a box below to place:

When iron rusts, it reacts slowly with water 💧 and oxygen 🌬️ from the air. This reaction involves the movement of electrons, which is why rusting is a redox reaction. In a redox reaction, one substance is oxidised (loses electrons) while another is reduced (gains electrons).

During rusting, the iron atoms at the metal surface first lose two electrons to form iron(II) ions, Fe2+. These two electrons are then used to reduce oxygen gas dissolved in the water, the product of this reduction reaction is the hydroxide ion, OH-. Next the Fe2+ ions are oxidised further to iron(III) ions, Fe3+. These ions go on to form hydrated iron(III) oxide – the brown, crumbly rust you can see.

To describe this clearly, chemists use word equations, symbol equations and half-equations. The most important ones for GCSE are summarised below in a sensible order.

So far all we have really talked about is the corrosion or rusting of iron and steel.

However, many other metals can also react with air (oxygen) and water and so corrode.

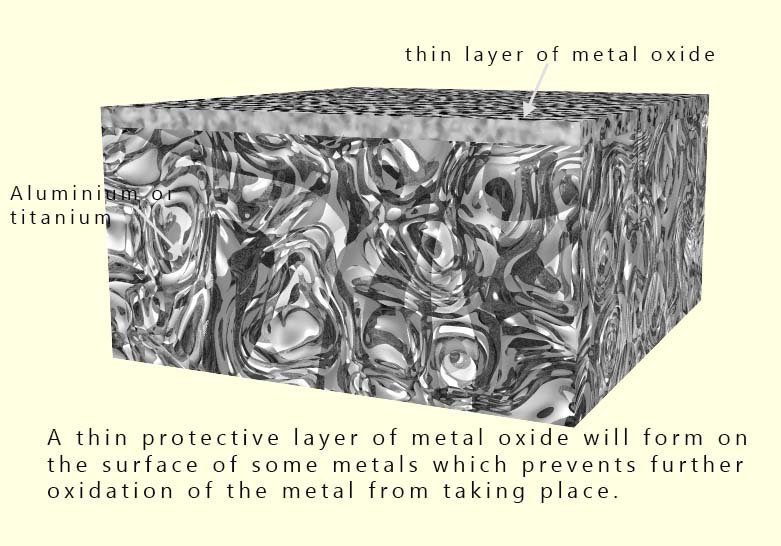

As an example, consider the two metals aluminium and titanium.

These metals, unlike iron, are more reactive, so you might expect them to corrode even faster than iron.

In reality, they appear to resist corrosion because both aluminium and titanium form a very thin,

protective, self-healing layer of metal oxide on their surface when they are exposed to oxygen.

This thin, transparent, non-porous oxide layer acts as a barrier, preventing more oxygen and

water from reaching the underlying metal and so preventing any further corrosion.

In reality, they appear to resist corrosion because both aluminium and titanium form a very thin,

protective, self-healing layer of metal oxide on their surface when they are exposed to oxygen.

This thin, transparent, non-porous oxide layer acts as a barrier, preventing more oxygen and

water from reaching the underlying metal and so preventing any further corrosion.

When iron corrodes, the rust formed on its surface is a soft flaky solid that falls off the outside of the iron. This then exposes more iron atoms which will quickly corrode. However, the aluminium oxide and titanium oxide layers that form when these metals corrode are hard, tough solids that seal off the layer of metal atoms below and effectively prevent the metals from undergoing any further corrosion. We can say they protect the metal from undergoing any further corrosion by basically sealing it from air (oxygen) and water.

This sealing of a metal surface to protect it from further

corrosion also occurs with copper.

Copper is a shiny bronze coloured metal which is often used to cover roofs in buildings such as churches and museums; indeed many large churches and museums have roofs made of

copper that have lasted for hundreds of years.

However you may not have spotted these roofs as they are green and not the shiny bronze colour you associate with copper metal.

The colour change from bronze to green is a result of the corrosion of the copper metal.

The copper is oxidised by oxygen and water in the air to form

copper oxide which further reacts with carbon dioxide and other pollutants to form a number of compounds, one of which is green copper carbonate.

Copper carbonate is one of the compounds responsible for the characteristic green patina seen

with many copper roofs.

Perhaps the most famous example of this is the Statue of Liberty in New York.

When the statue was erected in 1886 it was given a skin made of copper.

This would have been a shiny bronze colour but over the years the copper metal has corroded and turned a green colour or patina.

This patina consists of a number of compounds including copper carbonate.

The patina acts like a second skin and helps protect the copper underneath from undergoing further corrosion.