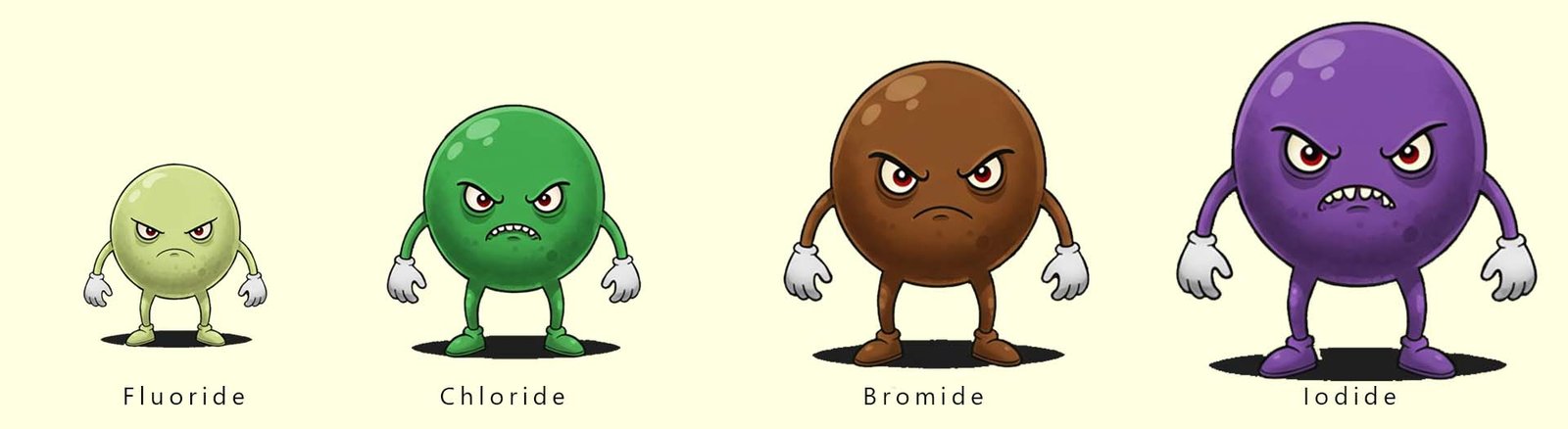

The halogens in their chemical reactions are generally good oxidising agents; that is they are electron acceptors; they oxidise other substances and the halogens are themselves reduced when they gain electrons. Displacement reactions using halogens are a good way to demonstrate the trend in the oxidising ability of the halogens.

Fluorine at the top of group 7 in the periodic table is the most

powerful oxidising agent in the periodic table, the trend in ability of the

halogens to

accept electrons and act as oxidising agents decreases as we descend group 7. Below we will look at the factors which affect the ability of halogens to act as oxidising agents.

To explain why the oxidising ability of the halogens decreases as we descend group 7 we need to consider a range of factors. Let's start by looking at the reduction reaction that occurs when a halogen accepts an electron and forms a halide anion. When a halogen oxidises a substance and is reduced we can show this very simply as:

Where X is any halogen. So which halogen is the best oxidising agent and why?

There are 3 factors you need to think about and which we will discuss below which will influence how good an oxidising agent a halogen is, these factors are:

| Halogen | F2 | Cl2 | Br2 | I2 |

| Bond enthalpy/kJmol-1 | 158 | 243 | 192 | 151 |

The bond enthalpies for the halogens drop as we descend the group; however this pattern does not hold for fluorine, its bond is much weaker than might be expected. This is a consequence of its small size; being so small its non-bonding electrons in the p-orbitals on each fluorine atom are relatively close to each other and this causes some repulsion between them which weakens the covalent bond.

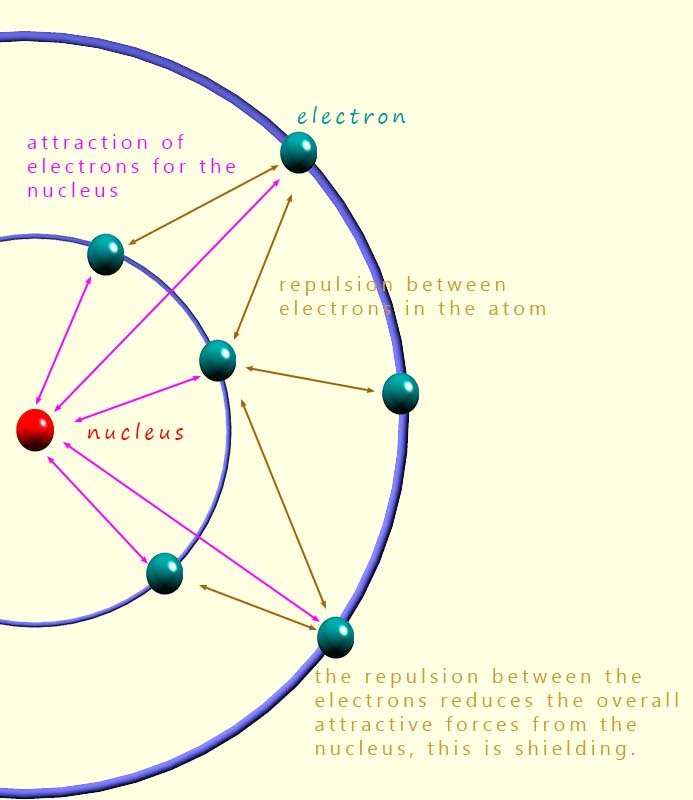

The second factor we need to think about when explaining the trend in oxidising ability is electron affinity. In simple terms, this tells us how easily a halogen atom can gain an electron and how much energy is released when that happens.

Whether a halogen atom can attract an incoming electron strongly depends on three main things:

Electron affinity is defined as the energy change for the following process:

The table below shows the electron affinity values for the halogens, that is, the energy change when 1 mole of electrons is added to gaseous halogen atoms.

| Halogen | F | Cl | Br | I |

| Electron affinity / kJ mol-1 | -328 | -349 | -324 | -295 |

At first glance, the electron affinity values for the halogens are actually quite similar. As we go down group 7, the nuclear charge increases which would tend to increase attraction for an incoming electron. However, this is offset by increased shielding and a larger atomic radius.

This effective nuclear charge is similar for all the halogens, but as we move down the group the atomic radius increases. This means the incoming electron is further from the nucleus for the larger halogen atoms and so feels a weaker attraction.

Fluorine, however, does not quite fit the general pattern. Its electron affinity is lower than you might expect. This is because the fluorine atom is extremely small, so any added electron must enter a compact 2p orbital. The close proximity of electrons causes extra electron–electron repulsion, reducing the energy released.

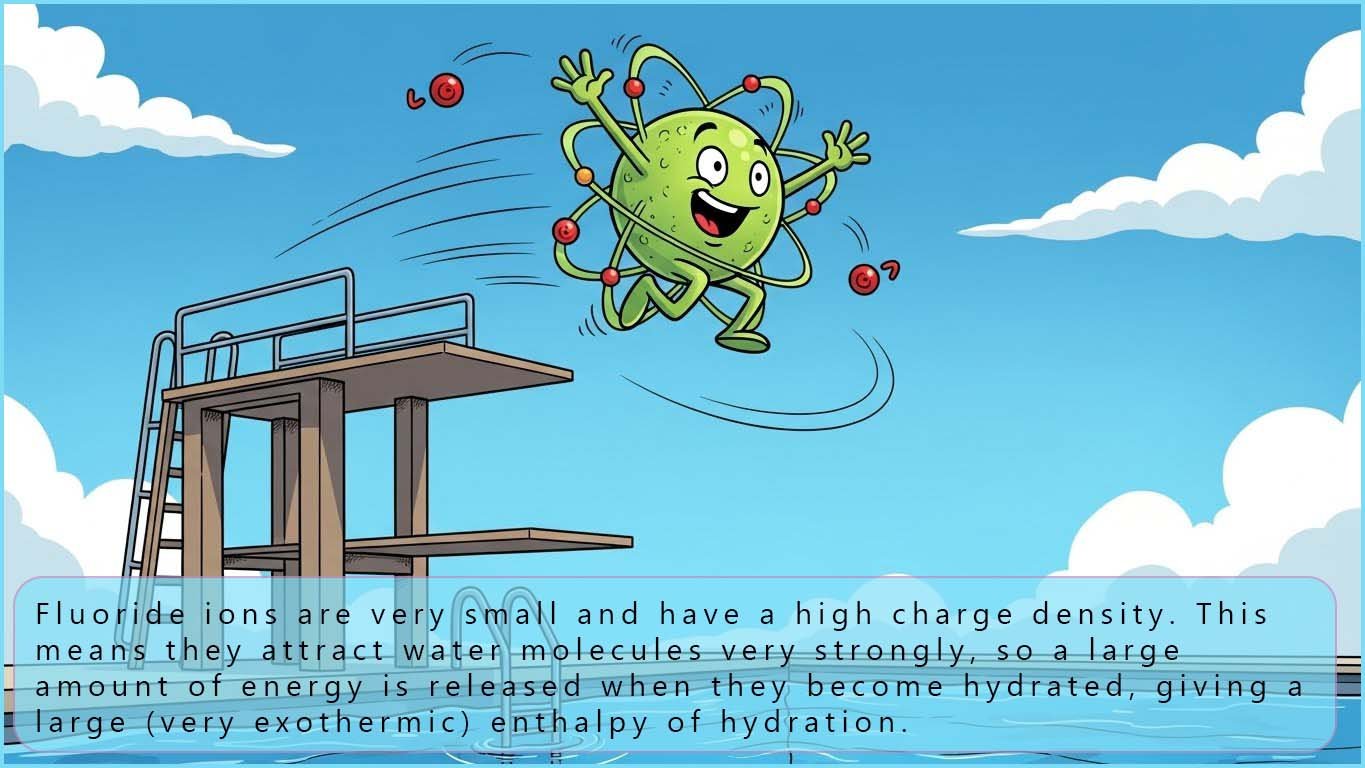

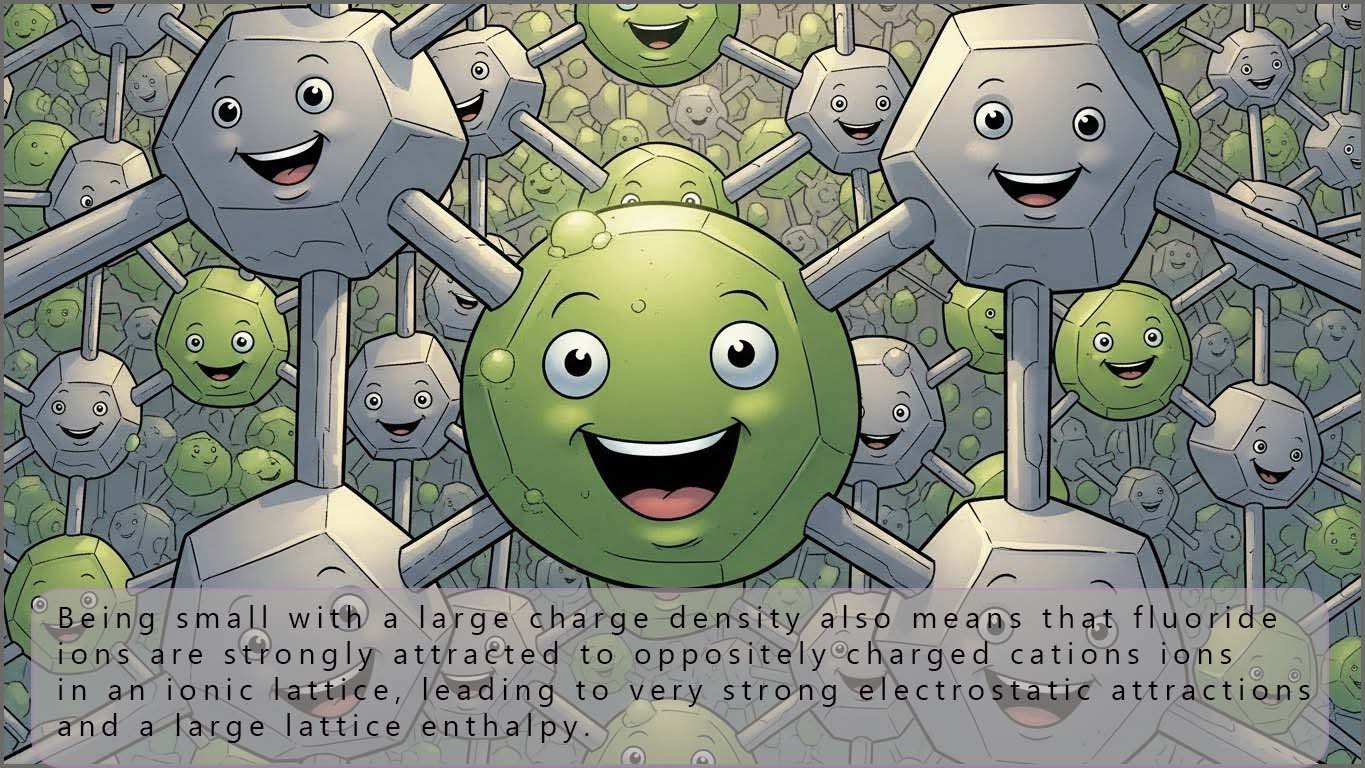

Finally, you should also consider the energy released when the halide ion formed goes into solution or forms part of a giant ionic lattice. We define these energy changes as:

This is summarised in the two images below:

Since all the halide ions have a charge of -1 the key factor here which will determine the size of the enthalpy change is the size of the ion. The smaller the ion the more energy will be released (more negative hydration enthalpy and lattice enthalpy) and so fluoride being the smallest halide ion will have the largest hydration enthalpy and lattice enthalpy.

Overall, the trend in oxidising power of the halogens is a balance between several factors. The weak F–F bond compared with the bond enthalpies of the other halogens, together with the large amount of energy released when fluoride ions go into solution or form part of an ionic lattice, explains why fluorine is the strongest oxidising agent in group 7.

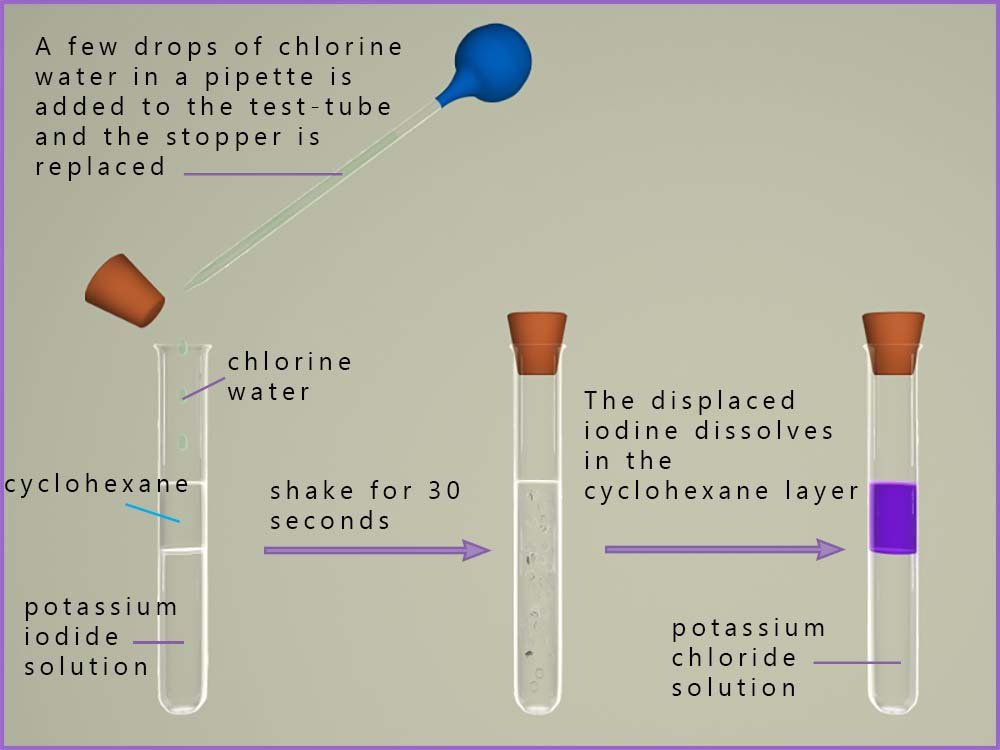

Displacement reactions are a good way to show the ability of the halogens to act as oxidising agents and to compare the oxidising ability of individual halogens. A typical displacement reaction is shown below. In the first test-tube there is a solution of potassium iodide dissolved in water. On top of this is added a few centimetres of an organic solvent such as hexane or cyclohexane. Cyclohexane is a very good solvent for the halogens and given the choice between dissolving in water and dissolving in cyclohexane a halogen will always dissolve in cyclohexane before water. Cyclohexane does not dissolve in water but like oil simply floats on top of it which is why there are two layers shown in the first test tube in the image below.

Potassium iodide being an ionic compound containing a group I metal ion will dissolve in water, this solution will contain potassium ions (K+) and iodide ions (I-). Now when chlorine water is added and shaken for around 30 seconds you can see that the cyclohexane layer changes colour to a violet/purple colour.

It may be easier to understand what is happening here if we write an equation for the reaction:

In a halogen displacement reaction the more reactive halogen will

oxidise the less reactive halide ion present. In this case chlorine

from the chlorine water will displace (oxidise) the iodide ion.

The iodine formed dissolves into the cyclohexane layer since the halogens are more soluble in organic solvents than in water.

Another advantage of using cyclohexane is that the halogens show up as bright, clear colours in organic solvents:

iodine is purple, chlorine is green/yellow and bromine is red-brown.

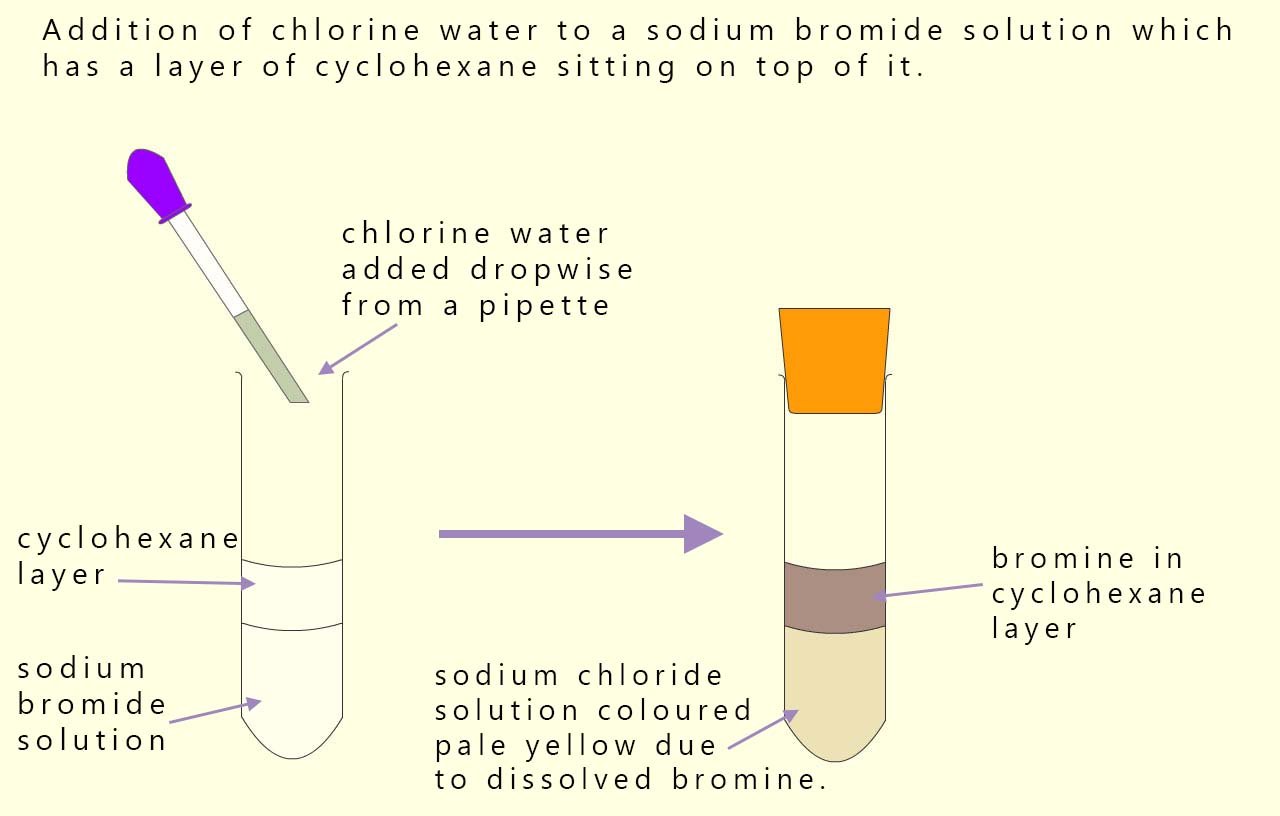

In the example shown below we again have one halogen and a halide ion present: a bromide ion from the sodium bromide solution and chlorine from chlorine water. Since chlorine is more reactive than bromine it will displace (oxidise) the bromide ion. The bromine formed dissolves in cyclohexane turning it red/brown.

We can show this displacement reaction using the equations below:

In these equations the chlorine has been reduced to chloride ions and bromide ions have been oxidised to bromine. Chlorine is the electron acceptor (oxidising agent) and the bromide ions are the electron donor (reducing agent).

However be careful as you can easily get caught out. Consider the reaction shown below:

Here we have iodine and chloride ions on the reactant side. Iodine is a poor oxidising agent and cannot oxidise the chloride ions, so no reaction takes place.

Pick a halogen and a halide solution from the activity below and predict if any reaction will occur:

1) Click a halogen. 2) Click a halide solution. 3) Read the result.

Displacement reactions are one way to show the oxidising ability of the

halogens, another method is their reactions with solutions containing Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions.

Iron(II) chloride solution is pale green while iron(III) chloride solution is pale yellow as shown in the image opposite.

We can demonstrate the oxidising ability of the halogens by reacting them with iron(II) chloride.

Chlorine and bromine are strong enough oxidising agents to oxidise Fe2+ to Fe3+.

and also:

The pale green Fe2+ solution changes to pale yellow Fe3+ when chlorine or bromine is added. This is not what happens with iodine. Iron(III) will oxidise iodide ions to iodine:

Here iodide ions are oxidised to iodine. A pale brown iodine solution forms along with a solid precipitate of iodine.

Use the activity below to predict if a halogen displacement reaction will occur and also practice writing out equations for the reactions taking palce.

Tap “New question”, then choose whether a reaction happens. If a reaction happens, pick the product halogen formed.