The group 7 non-metals are called the halogens. The halogens

are fluorine, chlorine, bromine

and iodine.

Astatine at the bottom of group 7 is a very rare and

a highly radioactive element; the most stable isotope of astatine has a half-life of just over 8 hours.

The halogens are

all very reactive elements and are not found as elements in nature; instead they are found commonly found combined in compounds

in rocks and minerals.

Fluorine, chlorine and bromine

all very toxic and corrosive elements and great care is needed in handling these highly reactive elements,

though iodine being the least reactive halogen and being

a solid is the easiest and safest halogen to handle in the lab.

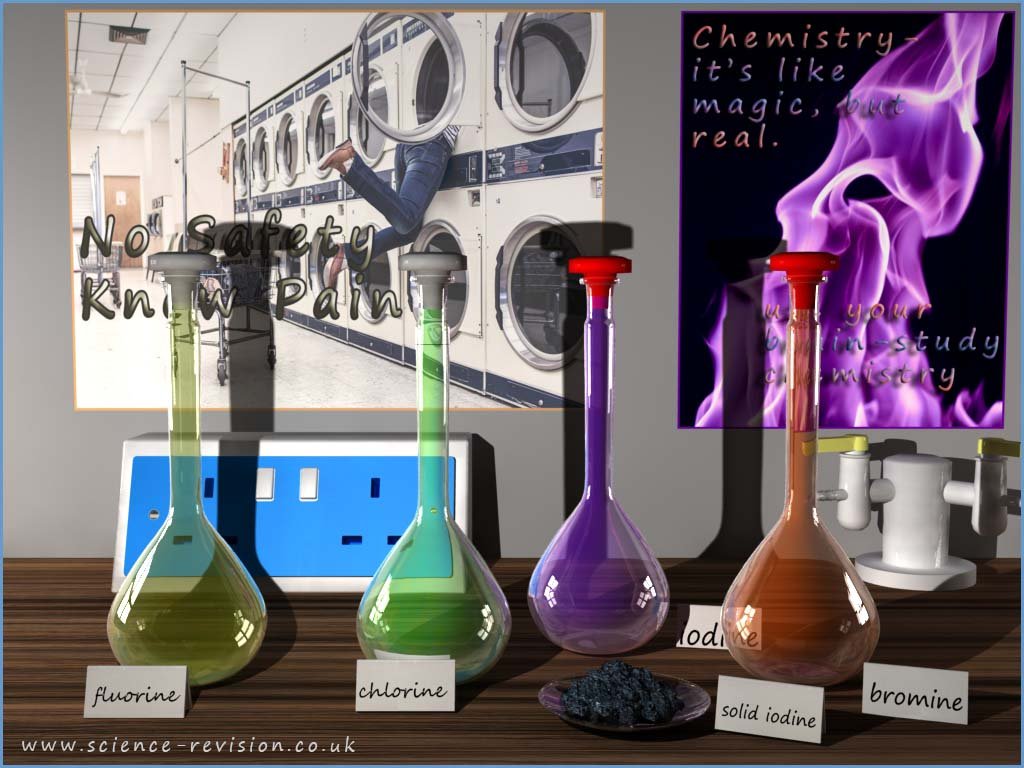

The image below shows the state and appearance of the first four halogens at room temperature.

Complete the activity below which highlights some of the dangers and hazards associated with the halogens.

Halogens and their compounds can be very dangerous. Read the safety description and choose the most appropriate hazard symbol.

Question 1 of 4

Cylinders of chlorine gas are labelled with a symbol showing a skull and crossbones.

Which safety icon best matches this description?

Common hazard symbols seen with halogens and their compounds: ☠️ Toxic, 🧪 Corrosive, 🔥 Oxidising, 🌊 Environmental hazard. Always check the label and follow lab safety rules.

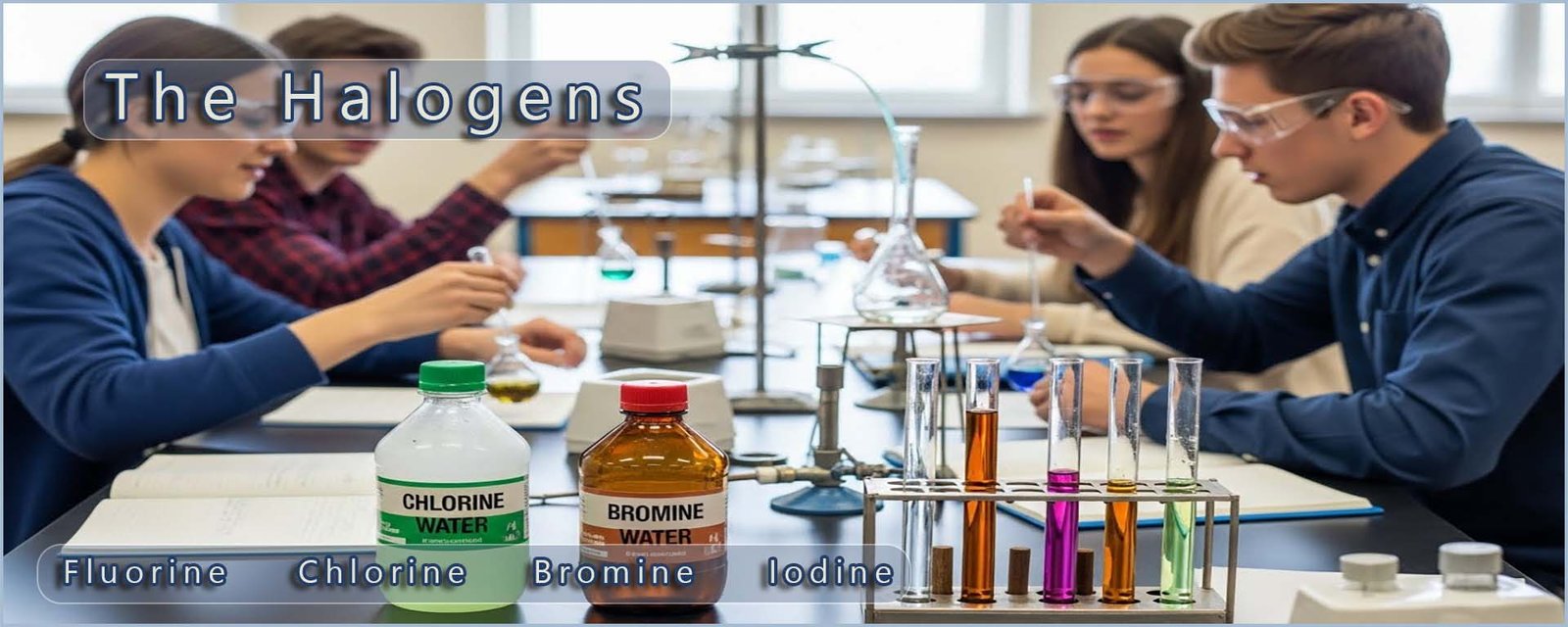

Click the button below then place the halogens in order of reactivity, most reactive first.

Click the halogens in order of decreasing reactivity. Start with the most reactive and end with the least reactive. Then press "Check my order".

Your order (1 = most reactive):

Tap each halogen to set the order:

Hint: reactivity and oxidising power decrease as you go down group 7. The most reactive halogen is at the top of the group, and the least reactive is at the bottom.

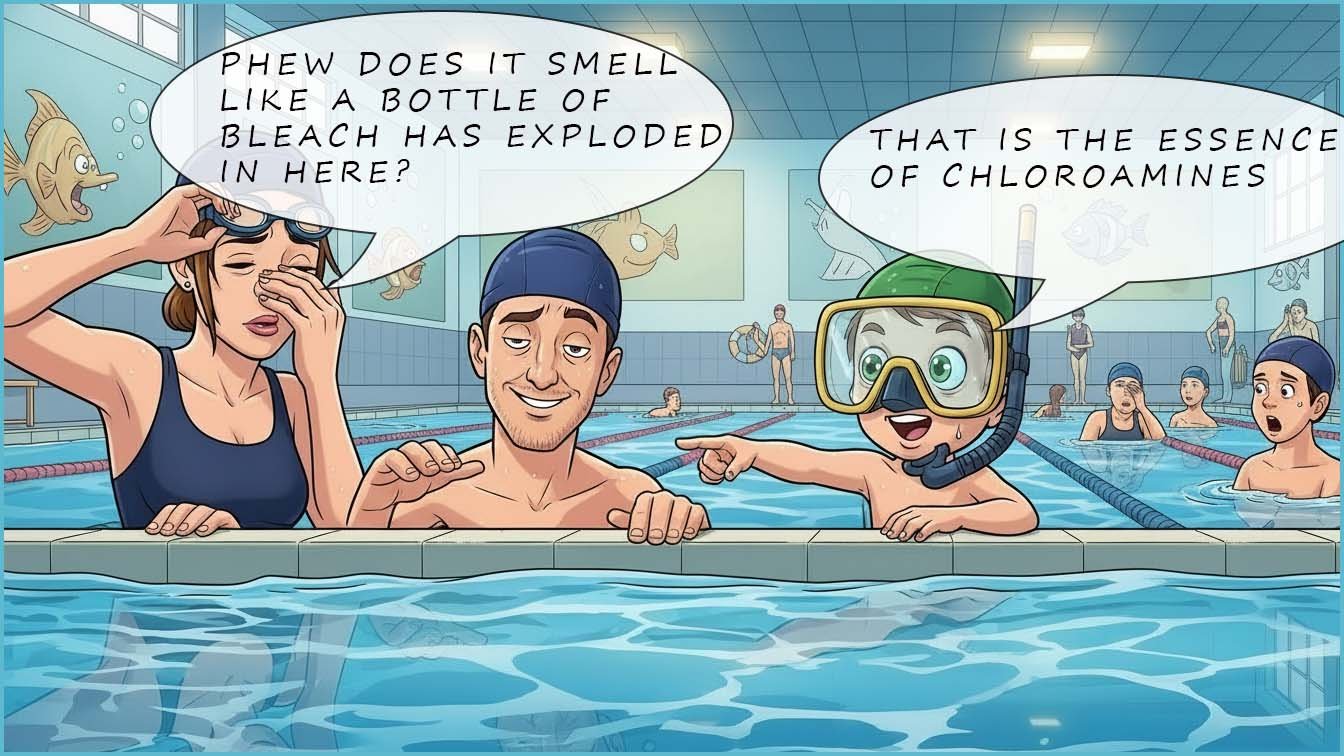

Fluorine at the top of group 7 is a very pale yellow-green toxic gas and is often described as the most reactive non-metal in the periodic table. It is so reactive it will attack glass and has to be stored in special containers. Just below it in group 7; chlorine is a greeny-yellow gas at room temperature that is also very toxic, corrosive and reactive. Chlorine has a very recognisable smell that most people associate with the swimming baths, but the “pool smell” is not actually chlorine gas as even small amounts of chlorine gas in the air would be highly dangerous. The smell at swimming baths is mainly due to chloramines, these are smelly by-products formed when chlorine in the pool reacts with nitrogen-containing waste from swimmers (sweat, urine, skin cells and cosmetic products).

It is these chloramines that are the primary cause of eye and nose irritation and the strong chemical smell commonly experienced at the swimming pool. One of the most volatile chloramines is trichloramine (NCl3), this leaves the water and irritates the mucous membranes of the eyes and the respiratory tract (nose, throat, and lungs) causing the irritation many experience at the swimming pool. A strong “chlorine” smell usually means the pool water is dirty and full of chloramines, not that there is too much chlorine in the pool.

Try the quick quiz below to review "the smell at the baths", just click the button to answer the questions.

Many people think a strong “chlorine smell” at a swimming pool means too much chlorine. Find out what is really happening.

1. A swimming pool has a strong “chlorine” smell. What is the most likely explanation?

2. Which change would usually help reduce the strong smell in an indoor pool?

Key idea: the “pool smell” is mainly caused by chloramines, made when chlorine reacts with nitrogen-containing waste such as sweat and urine.

Bromine is a volatile red-brown liquid at room temperature; if a small amount is placed in a flask it quickly evaporates to fill the flask with dense red-brown bromine vapour. Like fluorine and chlorine, bromine is very toxic and corrosive and has a sharp, bleach-like, choking smell.

Iodine is a grey-black crystalline solid with a metallic sheen at room temperature. On heating it sublimes, that is it turns directly from a solid into purple iodine vapour. Solid iodine and iodine solutions are used as antiseptics and iodine is also an essential element in the human diet for healthy thyroid function, so this apparently “dangerous” halogen is also found in antiseptic wipes and iodised table salt.

Simply click the buttons in the activity below for a quick re-cap on the properties of the halogens covered so far.

Tap or click a halogen to see its colour, state and a quick fact. Use this to help remember the trends down group 7.

Fluorine, F₂

Very pale yellow gas at room temperature. Extremely reactive and toxic. Fluorine is the most reactive non-metal and has the highest electronegativity in the periodic table.

Quick fact: fluorine is so reactive it can attack glass, so it must be stored in special containers.

Chlorine, Cl₂

Greenish-yellow gas at room temperature. Toxic and corrosive. Used as a disinfectant in swimming pools and for making bleach and PVC.

Quick fact: the “swimming pool smell” is not chlorine gas but chloramines, formed when chlorine reacts with sweat and urine.

Bromine, Br₂

Red-brown volatile liquid at room temperature. Its vapour is red-brown and very choking and toxic. It is the only non-metal that is a liquid at room temperature.

Quick fact: a small amount of bromine in a flask quickly fills it with dense red-brown vapour.

Iodine, I₂

Grey-black crystalline solid with a shiny metallic appearance. On heating it sublimes to give a purple vapour.

Quick fact: iodine is used as an antiseptic and is added to some table salt to help prevent iodine deficiency.

The halogens "go around in pairs"; that is they form small molecules made up of two atoms as shown in the image below. These diatomic molecules or two atom molecules are quite common for non-metal elements e.g. oxygen, nitrogen and hydrogen also form these diatomic molecules in their elemental state.

The data in the table below can be used to identify some of the trends in the physical properties of the halogens such as the trends in their melting and boiling points. The trend or pattern here is fairly obvious; as we go down the group the halogen molecules get larger and their relative mass molecular increases. Larger molecules with more electrons will results in stronger intermolecular Van der Waals bonding and this along with the increase in their relative mass will result in higher melting and boiling points.

| Halogen | Colour | Melting point/0C | Boiling point/0C | state at room temperature | outer electron configuration | atomic radius/nm | electronegativity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fluorine | pale yellow | -220 | -188 | gas | 2s22p5 | 0.071 | 4.0 |

| chlorine | greenish-yellow | -101 | -34 | gas | 3s23p5 | 0.099 | 3.0 |

| bromine | red-brown | -7 | 59 | liquid | 4s24p5 | 0.114 | 2.8 |

| iodine | greyish-purple | 114 | 184 | solid | 5s25p5 | 0.133 | 2.5 |

Recall that the electronegativity is the power or ability of an atom to attract the electron density in a covalent bond. Looking at the electronegativity values for the halogens in the table above the trend again is obvious:

To explain this trend we need to consider the factors which affect the electronegativity value for an atom, these are:

The electronegativity of any particular atom will depend upon a balance between these three factors:

From the electronegativity values given for the halogens we can say that the increasing size of the nuclear charge as we go from fluorine to iodine is more than compensated for by the increase in shielding of the nucleus as the atomic radius increases, this results in a drop in electronegativity as we descend group 7.

Click the button below to review the trends in the electronegativity values for the halogens

Click a halogen to see how its electronegativity compares to the others. The brighter the glow, the higher the electronegativity.

Fluorine, F₂

Chlorine, Cl₂

Bromine, Br₂

Iodine, I₂

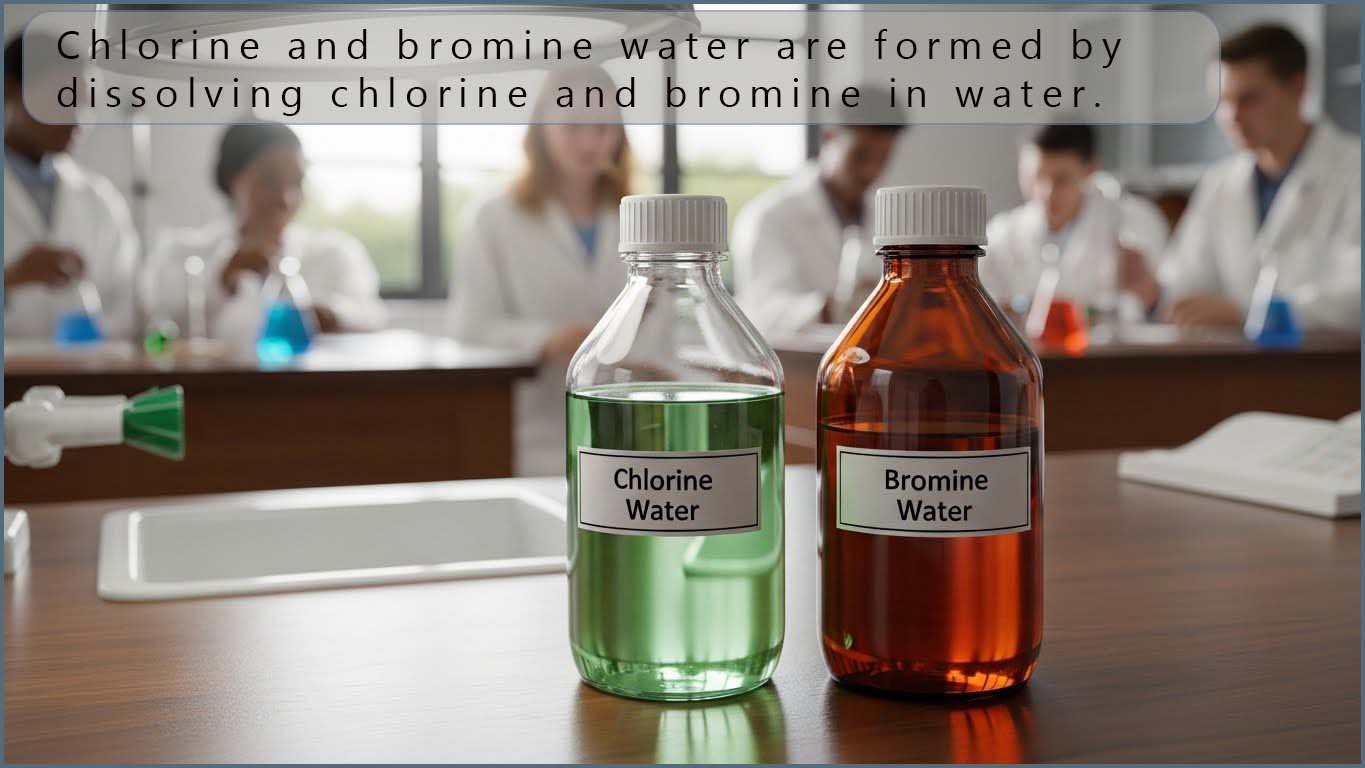

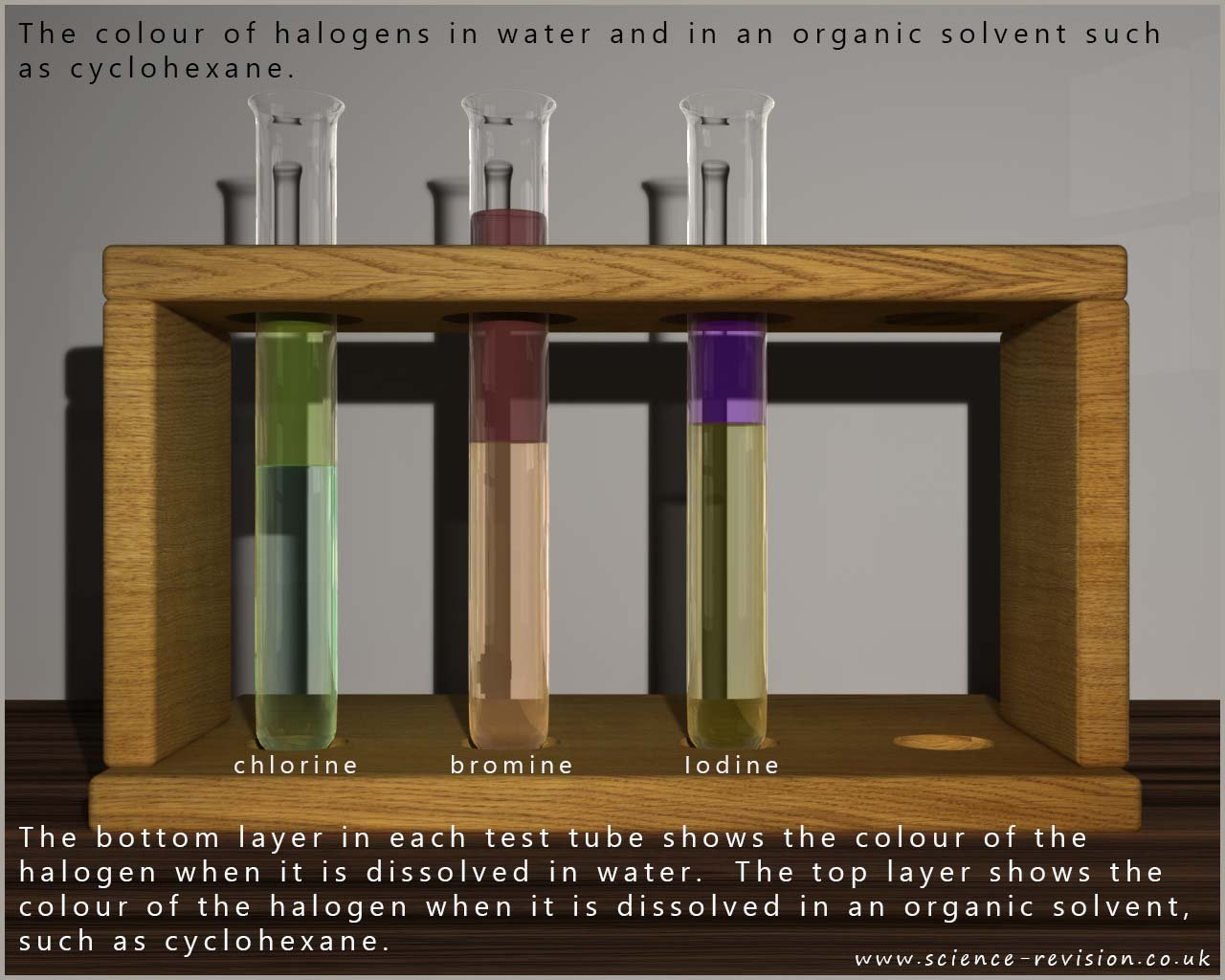

The halogens are all covalent non-polar molecules and as such are not particularly soluble in water; but they will readily dissolve in organic solvents such as cyclohexane or tetrachloromethane. Chlorine and bromine will dissolve and react with water to form a pale green and brown solution respectively. You will no doubt have used these two solutions in the lab before, they are simply referred to as chlorine water and bromine water. Both of these halogens react with the water in a reaction called a disproportionation reaction; here the chlorine and bromine are both oxidised and reduced. When chlorine dissolves in water it forms a mixture of the weak acid chloric (I) acid and the strong acid hydrochloric acid, equations for this disproportionation reaction are given below:

And for bromine dissolving in water we have:

The image below shows a bottle of pale green chlorine water and a bottle of brown bromine water, usually both of these solutions are stored in dark bottles since they will undergo photolytic decomposition reactions, that is they will break down in light, especially sunlight. The second image also shows a brown iodine solution, although iodine is almost insoluble in water; iodine solution is made by dissolving iodine in a potassium iodide solution.

Chlorine being an element has an oxidation state or oxidation number

of 0, but when it forms hydrochloric acid its oxidation state changes to -1

whereas in

chloric (I) acid the oxidation state of the chlorine is +1, this obviously means that the

chlorine has been both oxidise and

reduced in this reaction. Bromine

also undergoes a disproportionation reaction when it dissolves

in a very similar way to chlorine in water to form hydrobromic

and bromic (I) acids, equations for this reaction are shown above. Bromine is however less

soluble in water than chlorine.

Unlike chlorine and bromine iodine is practically insoluble in water so it will not undergo a disproportionation reaction; however it does dissolve in an aqueous solution of potassium iodide. When added to a potassium iodide solution the iodine molecules react with the soluble iodide ions (I-) to form triiodide ions (I3-). The solution formed is often labelled as iodine solution; as shown in the image above.

In the lab we may use a bottle of "iodine solution" which has a pale yellow colour when dilute but its colour becomes a dark orange-brown colour when its concentration increases. However despite limited solubility in water the halogens are very soluble in organic solvents such as cyclohexane.

If you need some more help with oxidation numbers then try the activity below; it shows how the oxidation state of the halogens change during disproportionation and halogen displacement reactions.

Click a reaction to see how the oxidation state of the halogen changes. Colours show the oxidation state of the halogen atoms in each species.

Chlorine with water – disproportionation

Cl0₂ + H₂O ⇌ 2HCl(Cl–1) + HClO(Cl+1)

Bromine with water – weaker disproportionation

Br0₂ + H₂O ⇌ 2HBr(Br–1) + HBrO(Br+1)

Chlorine displacing iodide ions

Cl0₂ + 2I–1 → 2Cl–1 + I0₂

Bromine with chloride ions – no displacement

Br0₂ + 2Cl–1 → no reaction

In organic solvents the halogens generally dissolve well to form solutions with bright clear colours. The rather dull brown colour of an aqueous iodine solution is replaced by a vivid purple solution when iodine dissolves in the organic solvent cyclohexane, as shown in the image below. Bromine also dissolves freely in cyclohexane to form a red-brown solution and chlorine forms a yellow-green solution when dissolved in cyclohexane; as shown in the image below:

Fluorine does not dissolve in water but instead reacts violently with water to form a mixture of hydrofluoric acid, oxygen and ozone (O3) gases.

Or if an excess of fluorine is used:

From what you learned in GCSE chemistry about electron arrangements we would have said that all the halogens have 7 electrons in their outer valence electron shell, or from your A-level work on electron configurations we can also say that all the halogens have a ns2np5 electronic configuration, this means they only need to gain one electron to achieve a full octet of electrons. This means that the halogens are used as oxidising agents, that is they accept electrons from other elements; they oxidise them and by accepting electrons they are reduced.

Use the activity below to complete the electron configuration for the halogens.

You will be given a halogen. Choose the correct atomic number and the correct electron configuration written in A-level style using noble-gas shorthand.

Target halogen:

Chlorine (Cl)

1. Choose the correct atomic number (number of protons):

2. Choose the correct electron configuration:

All halogens have 7 electrons in the outer p-block (ns²np⁵). More electron shells are added as you go down the group.

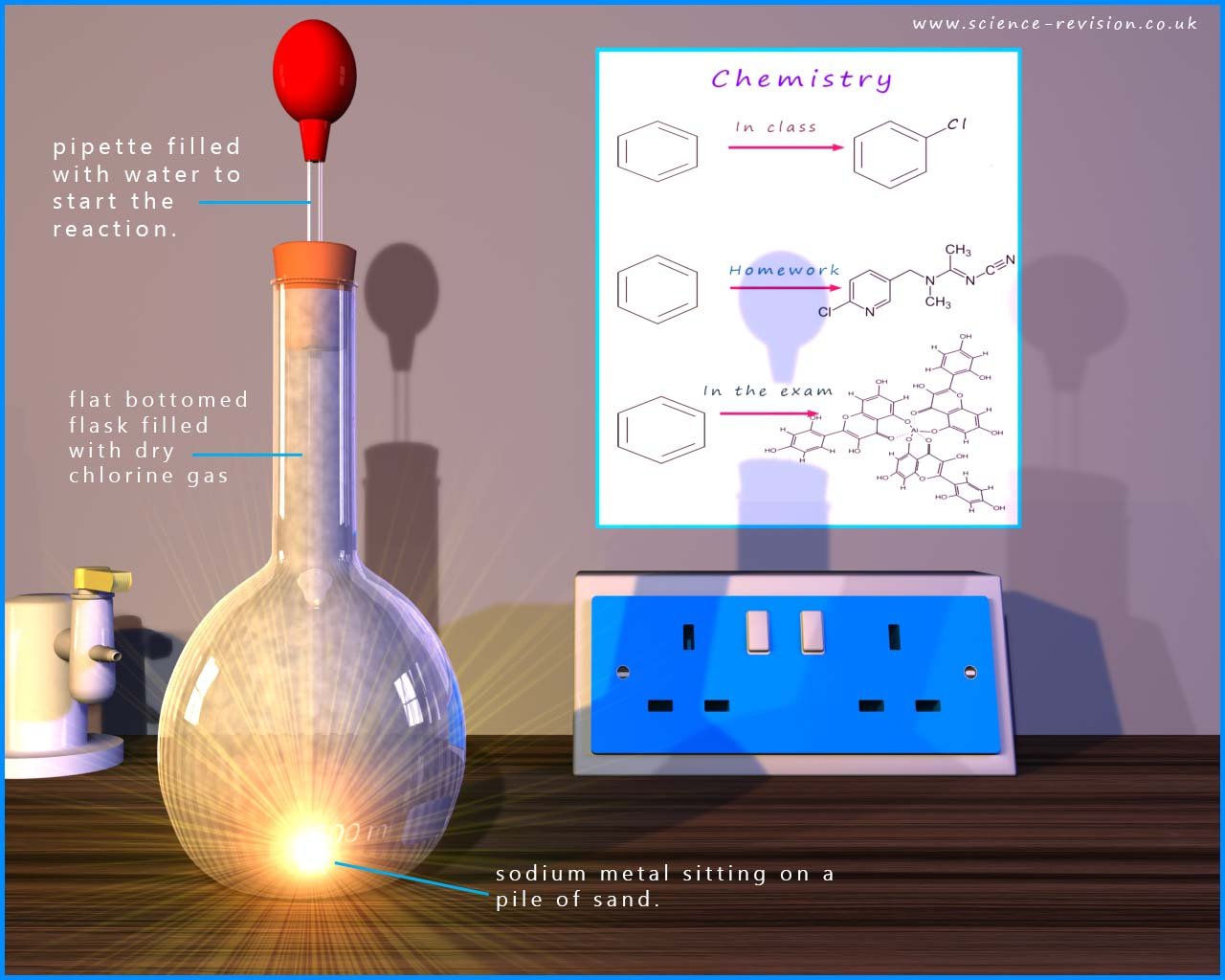

The reactions of the halogens with reactive metals such as those in groups I and II in the periodic table follow the trend you might expect, the more reactive the metal and the more reactive the halogen the more violent is the reaction. For example the alkali metal sodium reacts violently with chlorine to form the ionic compound sodium chloride, this is shown in the equations and image below:

And for magnesium:

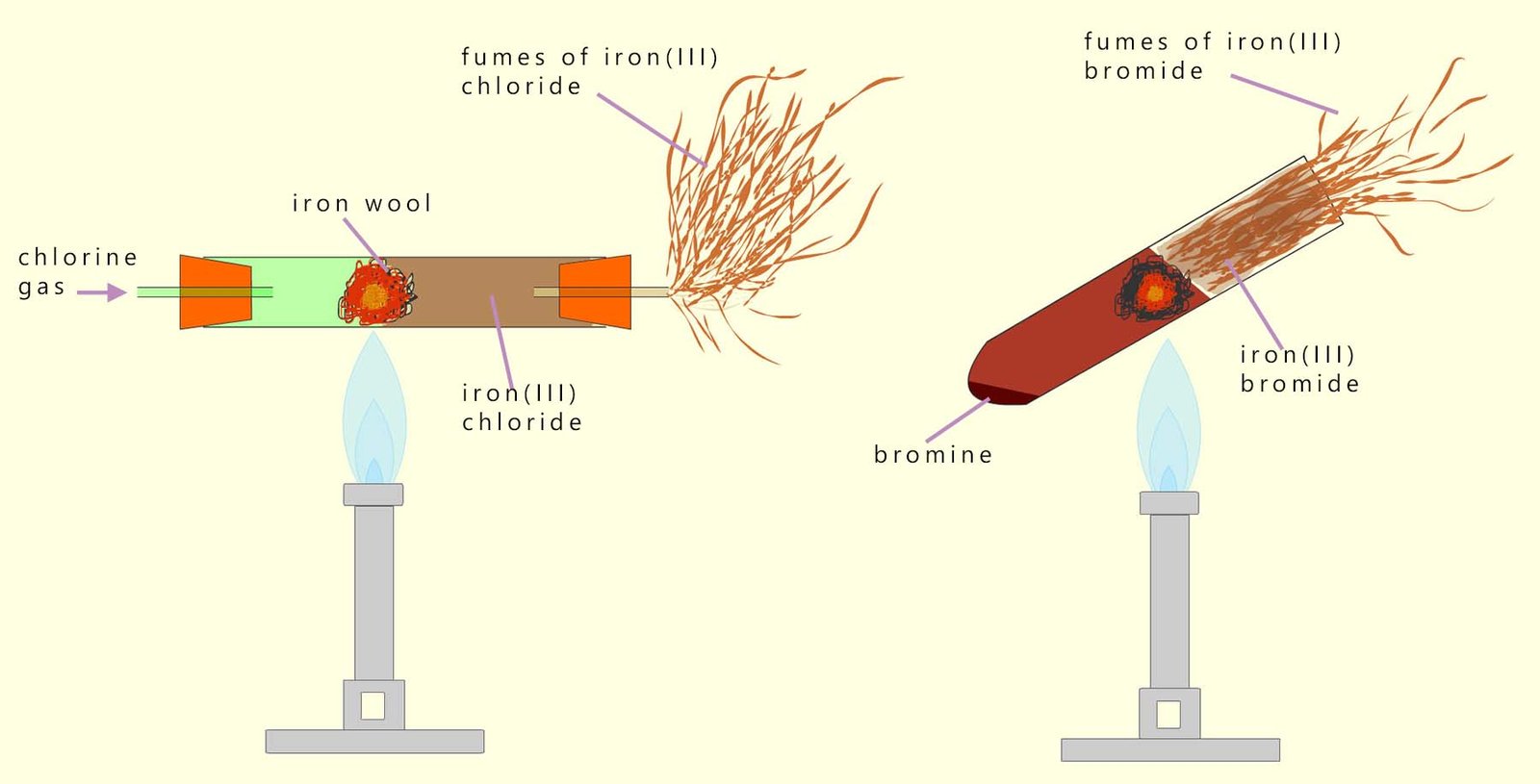

Even when less reactive metals such as iron (in iron wool for example) are used the results are the same; in each case the metal is oxidised and the halogen is reduced e.g. all the halogens react with iron wool. The trends in these reactions are as you would expect. The strongly oxidising fluorine immediately accepts an electron from the iron atoms in the iron wool. The products of the reaction are:

Similar reactions occur with chlorine and bromine. The image below shows the reaction of chlorine and bromine with iron wool to produce iron(III) chloride and iron(III) bromide.

The weakly oxidising iodine reacts much more slowly than chlorine or bromine and some considerable heat is needed to start the reaction. The other halogens all oxidise the iron to produce Fe3+ ions but the weakly oxidising iodine is only able to oxidise the iron to produce Fe2+ ions.

The trends here are exactly what you might expect:

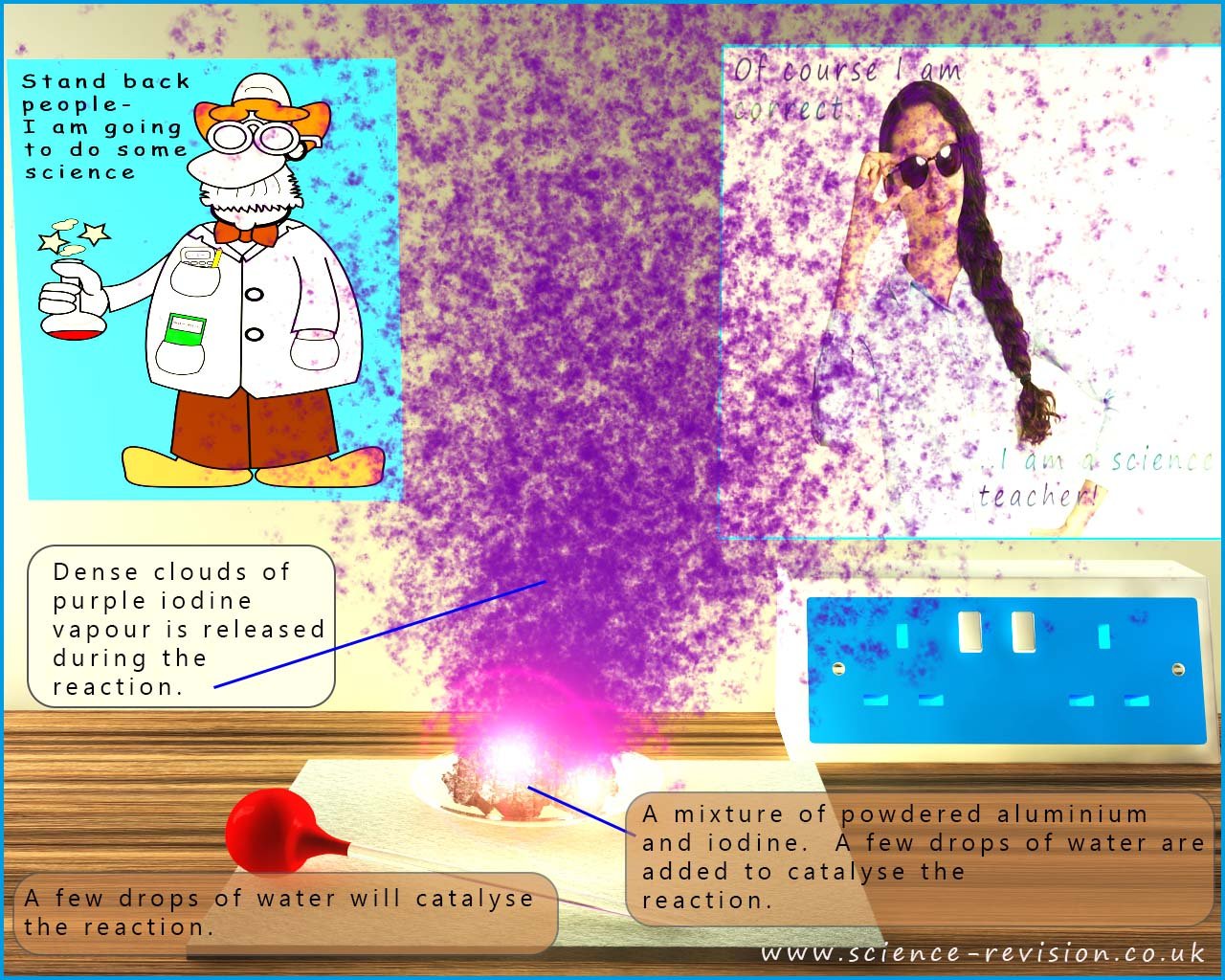

Perhaps some of the most visually spectacular reactions involving the halogens you are likely to see in school is in their reactions with aluminium metal. Here:

Fluorine being the smallest halogen atom will be able to attract a negatively charged electron from a metal atom more strongly towards its positively charged nucleus and so is the most reactive halogen. Iodine being in period 5 of the periodic table has 5 electron shells between its nucleus and any electron it tries to attract, these shells shield the positive nucleus from any electrons that it is trying to attract. The iodine nucleus may have a much larger positive charge than the small fluorine nucleus, but the effect of shielding and the fact that the nucleus is a long way from any electrons it may try and attract means that the ability to attract electrons decreases as you descend group 7.

Perhaps one of the best reactions to show the reactivity trends in the halogens is in their reaction with hydrogen gas. All the halogens react with hydrogen to form hydrogen halide vapours, as shown in the equation below:

E.g.

This trend in reactivity is due mainly is to the decreasing bond strength of hydrogen halides as you go down the group, which makes the formation of hydrogen halides less favorable energetically.

Choose a halogen and predict how it reacts with hydrogen gas, H₂. Think about how reactivity changes down group 7.

Halogen chosen:

Chlorine (Cl₂)

How will this halogen react with hydrogen gas, H₂?

Reactivity with hydrogen decreases down group 7. Fluorine is so reactive it explodes even in the dark. Chlorine also explodes but needs light or a spark. Bromine reacts only when heated with a catalyst. Iodine reacts very slowly and forms an equilibrium mixture.