📌 Exam tip

A very common mistake is to think that changing

concentration or

pressure changes the value of the

equilibrium constant (Kc).

These changes shift the position of equilibrium, but they do not change the value of the

equilibrium constant (Kc).

For a given reaction, the value of the equilibrium constant (Kc) only changes when the

temperature is changed.

A reversible reaction is one that does not go to completion, so instead of everything turning into products we are left with a mixture of reactants and products. In a closed system, the reaction can reach dynamic equilibrium, where both the forward and reverse reactions are still happening, but at the same rate.

You have already met Le Chatelier's principle, which is really useful for predicting the direction an equilibrium will shift when conditions such as temperature, pressure or concentration are changed. However, Le Chatelier's principle does not tell you how much of each reactant and product will be present once equilibrium is re-established.

This is where equilibrium constants come in. Rather than just telling us which direction the equilibrium lies, the equilibrium constant (Kc) allows us to put a number on the position of equilibrium. On this page, we will look at how the equilibrium constant (Kc) is used in practice. We will also look at:

Consider a reaction that we are all familiar with; the Haber process for the synthesis of ammonia gas:

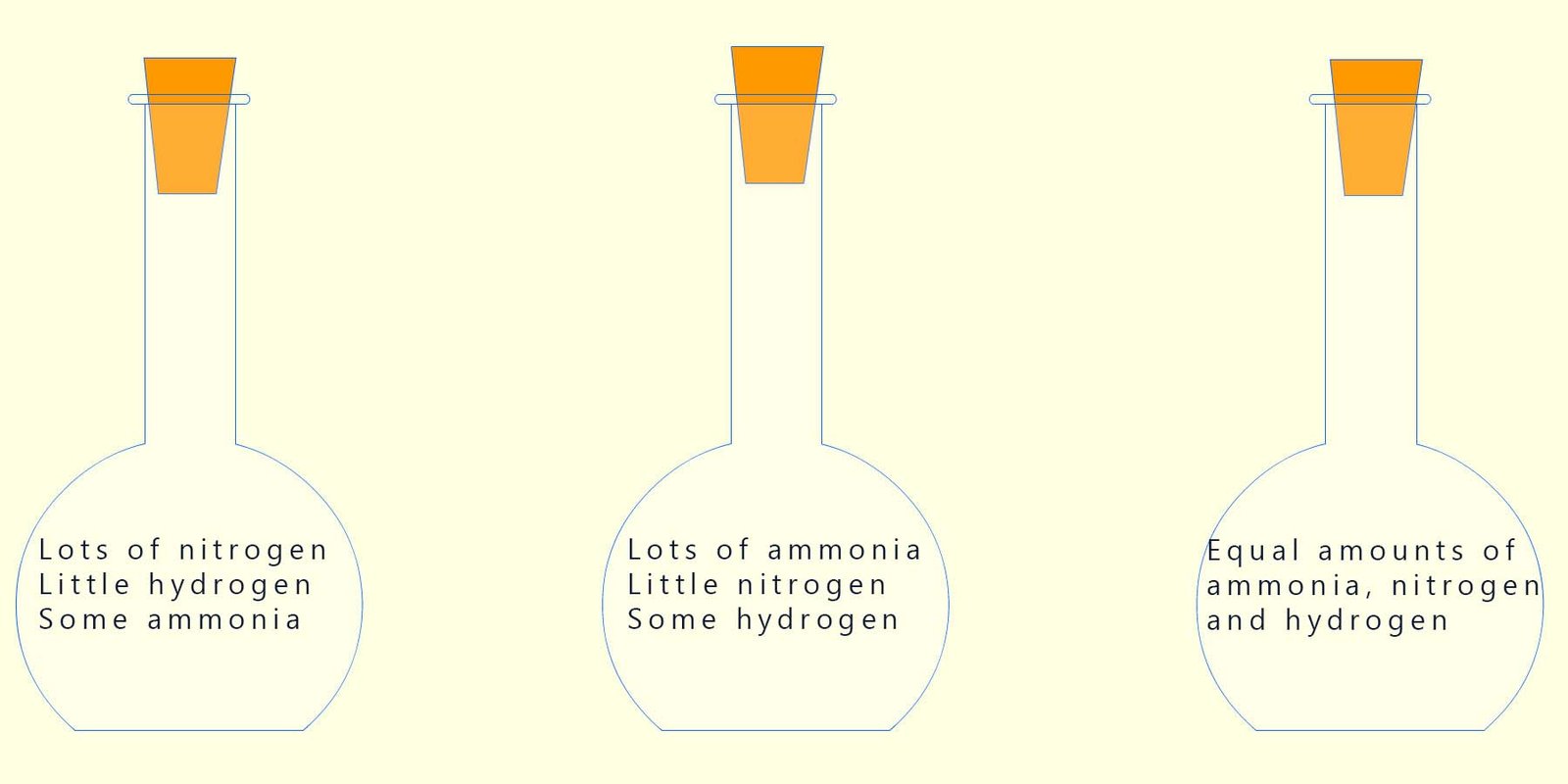

Now imagine setting up several flasks containing different amounts of nitrogen, hydrogen and ammonia, as shown in the image below. Even though the starting composition in each flask is different, if all the flasks are kept at the same temperature and allowed to reach equilibrium, something interesting happens...

So you are probably wondering what happens. Well we can say that:

Equilibrium can be approached from any direction; it does not matter whether you start with a flask filled with ammonia or one filled entirely with nitrogen and hydrogen. Given enough time to reach equilibrium, what we find is that there will be the same ratio of reactants to products at equilibrium, provided the temperature is the same.

The actual concentrations of the gases at equilibrium will not be the same in each flask. However, the ratio of the equilibrium concentrations, given by the expression [NH3]2 / ([N2][H2]3), will have the same value in every case. This constant ratio is what we call the equilibrium constant (Kc). Here the subscript c in Kc is short for concentration.

At this point you might be wondering where the ratio [NH3]2 / ([N2][H2]3) actually comes from. The key to answering this is to look back at the balanced chemical equation for the synthesis of ammonia. If you compare the numbers in the equation with the powers in the ratio, you should start to see the connection. This idea is not unique to the Haber process; in fact, we can say that in general for any reversible reaction at equilibrium:

Where A, B and C, D are the reactants and products, while a, b, c and d are the coefficients in the balanced equation. The expression for the equilibrium constant (Kc) for this reaction is given by:

Kc is the equilibrium constant and the subscript c refers to concentrations in mol dm-3. The square brackets [ ] are used to indicate that we are using concentrations in mol dm-3 for all of the reactants and products. The equilibrium constant is a ratio of the concentration of the products over the reactants, with each reactant and product concentration raised to the power of the coefficients in the balanced equation. So for the Haber process we can write:

This gives an expression for the equilibrium constant for the Haber process of:

The equilibrium constant is easily written from the balanced symbolic equation. For example consider the formation of sulfur trioxide gas from sulfur dioxide:

This gives an expression for the equilibrium constant for the formation of sulfur trioxide of:

As a final example consider the formation of hydrogen iodide gas from gaseous hydrogen and iodine; an equation for this reaction is shown below:

This gives an expression for the equilibrium constant for the formation of hydrogen iodide of:

From the examples above, you should notice that the concentration of the products (in mol dm-3) appears on the numerator (top line). The denominator (bottom line) contains the concentrations of the reactants (in mol dm-3). Each concentration term is raised to the power of the number in front of its formula in the balanced equation.

Have a go at writing expressions for the equilibrium constant for the reactions below; click the button to start.

Try these without looking back. Then check your answers.

The units of the equilibrium constant depend upon the stoichiometry (number of reacting moles) of the equation. For example consider the following reaction:

An expression for the equilibrium constant with units is shown below. Remember that for the equilibrium constant Kc all concentrations must be in mol dm-3. To work out the units of Kc replace each concentration term in the expression for kc with its units (mol dm-3) and then cancel out identical terms on the top and bottom lines just like algebra, this is outlined in the three examples below:

Example 2: Consider the following reaction:

This time in the equilibrium expression for A we have [A]2. We square the units of concentration:

(mol dm-3)(mol dm-3) = (mol2 dm-6).

As before, cancel out identical units from the top and bottom lines. The expression and units for the

equilibrium constant (Kc) is:

Example 3: Consider the following reaction:

The expression to work out the units for Kc is:

So far all of the examples we have looked at involve reactions where all of the reactants and products are gases or aqueous solutions. These are examples of homogeneous equilibria.

However, many equilibrium reactions involve substances in different physical states such as solids and gases. These are called heterogeneous equilibria.

In expressions for the equilibrium constant (Kc), pure solids and pure liquids are omitted. Only substances whose concentrations can change (gases and aqueous solutions) appear in the expression for Kc.

For example, consider the following equilibrium:

Although this equation contains three substances, only carbon dioxide is a gas. The solids calcium carbonate and calcium oxide are not included in the equilibrium expression.

This is because the concentrations of pure solids do not change during the reaction, so they have no effect on the value of Kc.

🤔 Common misconception

Students often try to include solids and pure liquids in a

Kc expression.

You leave them out because their “concentration” is effectively constant.

For example:

NH4Cl(s) ⇌

NH3(g) +

HCl(g)

Kc =

[NH3][HCl]

The solid NH4Cl is not included.

As another example consider the decomposition of solid ammonium chloride to form gaseous ammonia and hydrogen chloride gas:

Here, the solid ammonium chloride is omitted, so the expression for the equilibrium constant is simply:

Whenever you write an expression for Kc always start by crossing out any solids or pure liquids in the balanced equation.

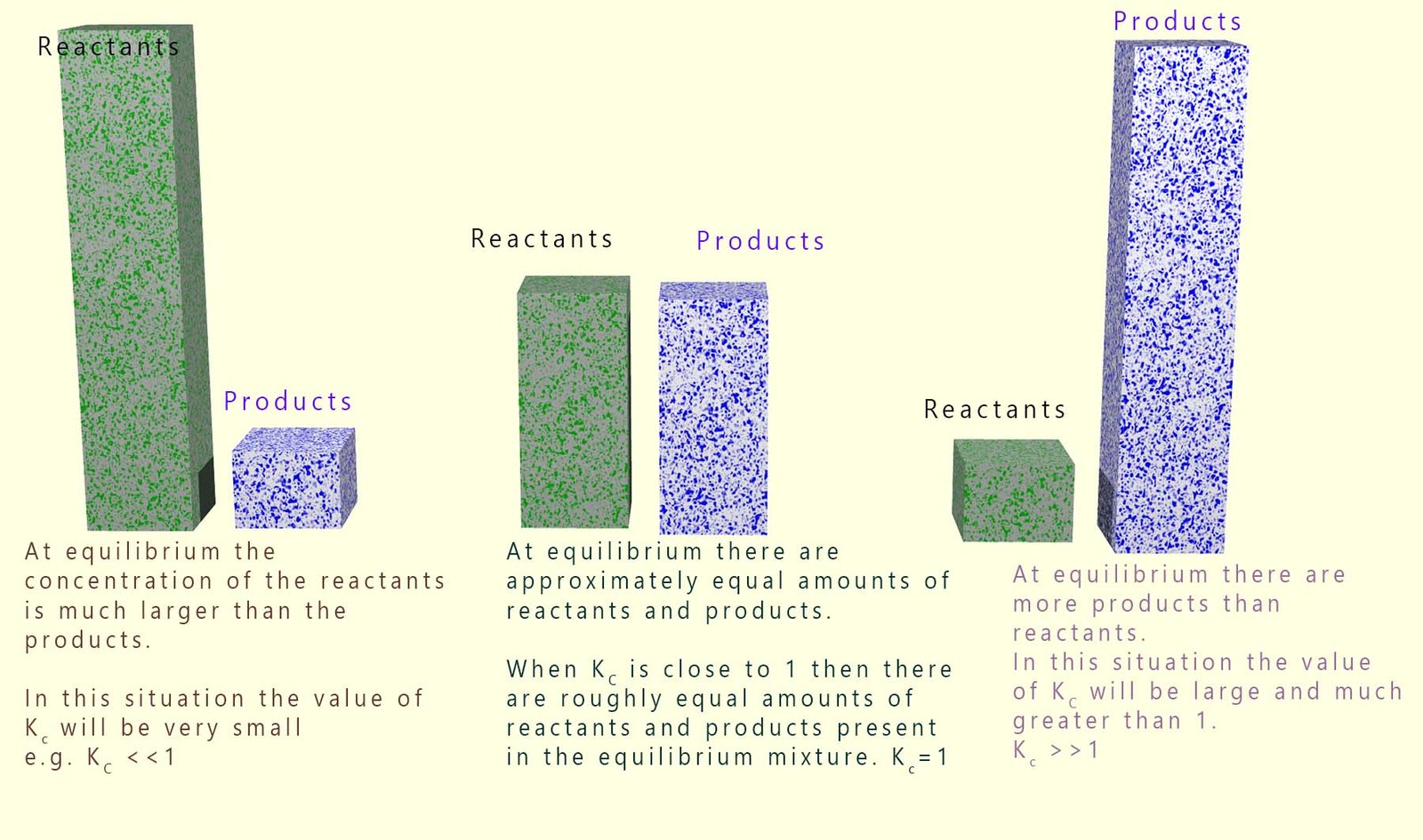

Since the value of the equilibrium constant (Kc) is the ratio of the concentration of the products over the reactants its value will give an excellent indication of whether there is more reactant or product present at equilibrium. The values of Kc vary tremendously; from very large numbers (for example 1 x 1050) to very small numbers (such as 1 x 10-20). These numbers give us a good indication of what is happening at equilibrium:

This is summarised in the diagram below:

You can use Le Chatelier's principle to predict how the position of equilibrium will change when reaction conditions are altered (for example changing temperature, concentration or pressure). However for a given reaction the value of Kc changes only when the temperature changes.

For example consider what happens to the value of Kc when the temperature is changed. Remember that Kc is the ratio of [products]/[reactants] at equilibrium, so when the temperature is changed ask yourself what happens to the equilibrium concentrations of the reactants and products. From this you should be able to explain what happens to the value of Kc.

As an example consider the reaction shown below:

Here the forward reaction is exothermic; this means the reverse reaction is endothermic. So what would happen if this reaction was at equilibrium and we changed its temperature?

You should still be able to use Le Chatelier's Principle to explain what happens to the position of equilibrium when the concentration or pressure is changed, but at constant temperature these changes do not change the value of Kc. This is discussed in detail on the page which deals with Le Chatelier's principle.

Have a go at these without writing out full expressions. Just decide what the final units of Kc will be.

Quick challenge: each expression below has one common mistake. Can you spot it? Click “Reveal” to check.

(1) For: A(g) + B(g) ⇌ C(g)

Wrong: Kc = [A][B] / [C]

(2) For: 2A(g) ⇌ B(g)

Wrong: Kc = [B] / [A]

(3) For: A(g) + 3B(g) ⇌ 2C(g)

Wrong: Kc = [C] / ([A][B])

(4) For: CaCO3(s) ⇌ CaO(s) + CO2(g)

Wrong: Kc = [CaO][CO2] / [CaCO3]

(5) Statement: “If I increase concentration, Kc increases.”

Wrong: True

If you can spot all five, you’re in great shape for exam questions on Kc.

A catalyst does not change the value of the equilibrium constant (Kc). It simply helps the reaction reach equilibrium faster.

This is because a catalyst increases the rate of both the forward and reverse reactions by a similar amount. So the system gets to equilibrium more quickly, but the final equilibrium concentrations (and therefore the value of Kc) are unchanged.

Decide whether Kc changes in each case. Click “Show answers” to check.

Key idea: Kc changes only when the temperature changes (for a given reaction). A catalyst changes the rate, not the equilibrium ratio.

🤯 Common misconceptions

✅ Myth: Changing concentration or pressure changes

Kc.

✅ Reality: These changes shift the position of equilibrium, but

Kc stays the same (as long as temperature is constant).

✅ Myth: At equilibrium the amounts of reactants and products must be equal.

✅ Reality: Equilibrium means equal rates forward and backward, not equal amounts.

✅ Myth: A big Kc means the reaction is “fast”.

✅ Reality: Kc tells you the position of equilibrium, not the speed.

Rate depends on things like catalysts and activation energy.